Satirino records · A Cleare Day

Pieces from the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book

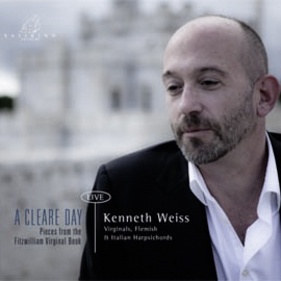

Kenneth Weiss Virginals, Flemish & Italian Harpsichord

Satirino records SR111 - released on 23rd March 2011

Live recording

at the Centre Culturel de l’Entente Cordiale – Château d’Hardelot

Midsummer Festival, 19 & 20 juin 2010

Instruments

Italian Virginals

by Jean-Luc Wolfs-Dachy (Happeau-Lathuy / Belgium, 2006) after Alessandro Bertolotti (Verona, 1585)

Single manual Flemish harpsichord

by Marc Ducornet (Paris, 2005) after Johannes Ruckers (Antwerp, early 17th Century)

Italian harpsichord

by Marc Ducornet (Paris, 2007) after C. Grimaldi (Messina, 1697)

Tuning

François Ryelandt - ¼-comma meantone

Sound engineer, producer, editing, mastering

Jiri Heger

Design

le monde est petit

Images

© Arthur Forjonel

Thanks to

Sébastien Mahieuxe, Conseil Général du Pas de Calais, Centre Culturel de l’Entente Cordiale - Château d’Hardelot, Éric Gendron & toute son équipe technique, Jiri Heger, François Ryelandt, Aline Pôté, Arthur Forjonel & Supercloclo

Coproduction

Centre culturel de l'Entente cordiale - Château de Hardelot

Conseil Général du Pas de Calais

Press Reviews

'A superbly recorded live CD, this album demonstrates remarkable subtlety of touch and phrasing. With his admirable capacity for rhythmic stability, Weiss masters the sheer virtuosity and throws new light on the almost orchestral polyphonic complexity of this music. He transcends the interminable harmonic scrolls to hypnotic heights... A powerfully imaginative reading by an musician at the zenith of his art.

'Philippe Ramin,

Diapason, June 2011

'Kenneth Weiss enlightens every detail, delivers torrents of notes, in a mixture of brilliant daring profound contentment. This is High art.'

Michèle Fizaine, Midi Libre, April 2011

'In short, this is an excellent CD: it has excitement, originality, real beauty in the sound, and interest in the interpretations. There is strong evidence of personal style at work, but it is intelligently applied to suit the varying character of the music, and so is logical and convincing. The entire recital is hugely enjoyable. No one who is keen on early keyboard music should be without this disc; but such is the variety and attractiveness in the programme, the styles of performance, and the sounds of the instruments, that it should also please and stimulate the general listener.'

The Thomas Tomkins Forum, April 2011

Liner Note

Gaze out of a casement window in an English manor house and on some days you couldn’t miss those rapid changes from ‘faire’ to inclement weather so quaintly captured in Mundy’s Fantasia from which the present recording takes its title. Such are the vicissitudes of English weather: the result of our prevailing South-Westerly wind. How imaginative of this somewhat elusive composer to portray this on the virginals in a clear high tessitura with a touch of ‘eye-music’: white notes for the passing clouds, and black for the bursts of thunder, portrayed by bass-register runs and clashing chords. It’s a true fantasia just as the composer Thomas Morley characterised the genre in his Plain and Easy Introduction to Practical Music of 1597:

... the Fantasy, that is when a musician taketh a point at his pleasure and wresteth and turneth it as he list, making either much or little of it according as shall seem best in his own conceit ...

Hypotheses and their demolition surround the history of the ‘Fitzwilliam Virginal Book’, so labelled after the wealthy nineteenth-century benefactor Richard Fitzwilliam, seventh Viscount of Merrion, who founded the celebrated museum in Cambridge bearing his name. Here is where the manuscript is to this day deposited, acquired by Fitzwilliam from a music dealer Robert Bremner who had bought it for the sum of ten guineas at the sale of the composer Dr. Pepusch in 1762. The singer Margherita de L’Épine, Pepusch’s wife, was renowned as a performer at least of some of the easier pieces from the book: an interesting fact since it confirms their popularity even as late as the eighteenth century. But she was apparently not up to the trickier pieces, such as the formidable Walsingham variations.

The adopted title for this anthology thus signals no link to the history of its compilation. How much rosier would it have been if the name by which it was known in Victorian times could have stuck! Until the monumental edition of the collection appeared in the last years of the nineteenth century it had been referred to as ‘Queen Elizabeth’s Virginal Book’: a name which conjures up not only a golden courtly era, but also something of the social place of keyboard music at the turn of the sixteenth century.

Sumptuously bound in crimson morocco with gold tooling and finely-gilded fleur-de-lys, it’s certainly a volume fit for a monarch. But the two editors of the collection, Fuller Maitland and Barclay Squire, pointed out in their copious preface that Elizabeth, who died in 1603, could not have owned it, not least because there are several items dated from after her death, the latest being a piece by Sweelinck dated 1613. On the other hand, many of the pieces are recopied from earlier collections, so she might well have known some of its contents.

Certainly she played the virginals. One Sir James Melville, an ambassador from Mary Queen of Scots has a delightful memoir of eavesdropping on Queen Elizabeth dating from 1564:

after dinner my Lord of Hunsdean drew me up to a quiet gallery [ ... ] where I might hear the Queen play on the virginals [ ... ] I entered within the chamber, and stood a pretty space hearing her play excellently well, but she left off immediately, as soon as she turned about and saw me.

If this reminiscence is of little relevance to her ownership of the collection it does give us some hint of the intimate place which keyboard music occupied within the higher echelons of court society at the turn of the sixteenth century: a time to be alone; to remind oneself, artfully, of popular tunes and dances, both refined and vernacular, and to perfect one’s art by playing music which is often extremely tricky.

When we delve into the history of the manuscript we find more hypotheses and more dispute. Certainly a family of Cornishmen were deeply implicated in its assembly: a father and son both named Francis Tregian, the pair of them Catholic recusants successively incarcerated in the Fleet prison for their beliefs. The evidence is strong enough for the suggestion of a more appropriate title for the collection: ‘The Tregian Manuscript’, perhaps.

Tregian the younger (1574–1617) has been credited with the task of copying the entire manuscript by its first editors who put forward the hypothesis that he whiled away his 20-odd years in the Fleet prison with this heavy labour. Only relatively recently a subsequent scholar found an example of Tregian’s signature on a document in a library in Truro in Cornwall, near the original family properties which had been seized as part of the punishment of the elder Francis Tregian. It matched the Francis Tregian abbreviation often found in the Virginal Book.

But further questions remain: how he could have had access to all the manuscript sources while imprisoned? Another theory is that the manuscript, while Tregian had a hand in it, was actually put together by a ‘scriptorium’—a team of copyists. But here, too, questions may be raised. What was its purpose? And who paid for it?

So much for its origins. How important is it as a source, and what characterises its contents? The first question can be simply answered in stressing its unparalleled richness. For many of its pieces it is not the only source but there are notable exceptions, especially in the case of the music by Giles Farnaby. It is mostly of English music though it reflects the cross-continental activities which so deeply affected the course of music at this time, with some pieces by Italian composers; some transcriptions (known as keyboard intabulations) based on Italian music—both celebrated songs and madrigals—and with some pieces by Flemish composers, notably the Dutch keyboard master Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck.

After Mundy’s ‘meteorological’ Fantasia comes a tribute piece to John Dowland, whose lute-song ‘Flow my tears’, and related consort pieces Lachrimae or Seven Teares, enjoyed tremendous popularity at the turn of the sixteenth century. Here we have a keyboard version by Byrd, styled as a Pavana: perfection itself in the way the tune is surrounded by expressive counterpoints which always have a clear direction and are beautifully crafted. Sparing lute-like chords accompany—this type of texture is often referred to as the ‘style brisé’ or ‘broken style’. Occasionally Byrd takes our breath away with a higher-register flourish of poignant beauty, especially telling on the virginals. Here the piece is paired with a Galliard in the same key from elsewhere in the book: a typical pairing of what Morley called ‘a kind of staid music, ordained for grave dancing’ (the Pavan) while noting that ‘after every pavan we usually set a galliard [ ... ] causing it to go by a measure which the learned call ‘trochaicam rationem’ consisting of a long and a short stroke successively’.

Peter Philips’s intabulation of another popular hit, Giulio Caccini’s ‘Amarilli mia bella’ could hardly be more contrasting. Philips was himself most active as a madrigalist as well as being ‘very cunning’ on the virginals. The poem is typically Baroque in its physicality: the poet offers Amaryllis an arrow to open his breast: she will see written on his heart ‘Amaryllis is my love’. Caccini’s setting, with its rising vocal line and intensifying harmonies, mirrors the emotional crescendo of the poem. Philips’s keyboard setting follows suit, with repeated, full chords intensifying the imagery of the final lines.

The Anonymous ‘Why aske you’, elsewhere credited to Farnaby, is typical of the simpler, shorter pieces of the collection where the distinction between a Ground bass, with a simple repeated pattern of chords, and that of the Variation is blurred. The piece is catchy and has a chain of suspensions at the end: ideally suited to bring a touch of dissonance into the short-lived but silvery tones of the harpsichord.

‘Woody Cock’ is similarly an easy tune, but it is treated in a far more elaborate way. More like the pieces of Tomkins and Bull, its set of six variations do not stick with one idea for each variation, but constantly bring in successions of new ideas to elaborate the simple chordal patterns which accompany the tune when it is first presented. This piece introduces a further element common to the more extended variations in the book: a sense of the cumulative, of rising excitement, sometimes obtained by complexity, sometimes by virtuosity. In this piece there’s a bit of both, with triplet figurations playing a considerable part.

Orlando Gibbons’s Pavan may remind us of Byrd’s ‘Pavana Lachrymae’ in two ways: firstly it has a similar opening, as if even the opening shape of Dowland’s ayre had been absorbed into the bloodstream of the early years of the new century; secondly, it is again classical in the way its inner lines are shaped within gently rolled chords. The way it ends is very striking: a series of sequences descend to the final chord for which the low A of the instrument has been saved, giving a particular and surprising depth.

Byrd’s variations on the triple-time ‘The Woods so Wild’ establish the simple tune at the beginning of the piece and bring it back at the end. In between we hear hints of its shape, sometimes in canon. In the final fourteenth variation it returns more fully-clothed than before, with more chords to harmonise it.

Martin Pearson’s tiny couple of Variations ‘The Fall of the Leafe’ makes use of low-register chords to keep up a particular fullness which pervades the piece: one of the delights of the simpler pieces in the collection.

Who Barafostus was is something of a mystery. There are two settings of his tune in the collection, an anonymous one is simple and relatively short. Tomkins’s setting is quite the reverse with some of its keyboard ideas presaging a future generation. There are contrary-motion arpeggios, zig-zag figurations and almost Alberti-basses. In this respect, Tomkins has an imagination rivalled only by Bull and Byrd.

Several Almans are to be found in the book and Byrd’s ‘Queen’s Alman’ is a fine example of this moderate duple form often danced in couples. As is so common with Byrd, the passage-work is beautifully crafted, though this is more a chordal than a contrapuntal piece.

Ferdinando Richardson seems to have been a pupil of Tallis. Very little of his music survives but this Pavana and Galiard with a variation on each is extraordinary both in its form and its execution. One of the fleetest in the collection it notably plays with hemiolas: syncopated triple rhythms noticeable in both the Galliard and its variation.

To end is John Bull’s monumental set of thirty variations on Walsingham, complementing the twenty-two composed by Byrd, which appear elsewhere in the collection. There is no way in which they could be strung together since they are in different keys but there may be an element of rivalry here. The extraordinary fertility of mind and fleetness of fingerwork, including a rare example of cross-hands writing, bring this brief but immensely varied selection to a most appropriate culmination.

Richard Langham Smith

Note by Kenneth Weiss

The three instruments I have chosen for this recording were all common in England at the turn of the sixteenth century, the term ‘virginals’ being a generic word encompassing any plucked, stringed keyboard instrument of the time. My wish is to show the wealth of sonorities that inspired these composers while giving today's listeners an opportunity to discover each instrument’s specific character.

Because of the rectangular shape of the virginals, its strings run parallel to the keyboard and are plucked close to the middle of the string. The sound that results has a rich, flute-like tone. The shape of the instrument also means that the sound is projected directly to the player creating an intimacy similar to that of the clavichord. As indeed much of this music was meant primarily for the player to enjoy, rather than for public performance, I chose to perform the more reflective, intimate pieces on this instrument.

The Flemish harpsichord, with its slender soundboard and two sets of strings–one an octave higher than the other–produces a brighter, more resonant sound. I used this instrument for the more boisterous pieces, its effervescence a perfect partner to project their vitality.

The Italian harpsichord, with its relatively light string tension, produces a strong attack that drops off rather quickly. This instrument is best suited to the more rhythmic, technically demanding and contrapuntal pieces, giving a clear delivery while not accumulating too much residual sound.

The unprecedented inventiveness and virtuosic ingenuity of the composers found in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book both ask and answer the question of what the keyboard can achieve. Their art, four hundred years later, is a testament to the beauty and endurance of keyboard literature.

Kenneth Weiss

Track list

(1) Virginals

(2) Flemish harpsichord

(3) Italian harpsichord

1 - John Munday c1555 - 1630

Fantasia (2) - 3’55

Faire Wether, Lightning, Thunder, Calme Wether, Lightning, Thunder, Faire Wether, Lightning, Thunder, Faire Wether, Lightning, Thunder, A cleare Day

2 - John Dowland 1563 - 1626 set by William Byrd

Pavana Lachrymae (3) - 5’31

3 - William Byrd 1542? - 1623

Galliard (3) - 1’28

4 - Peter Philips c1560 - 1628

Amarilli di Julio Romano (1) - 3’29

5 - Anonymous

Why aske you (1) - 1’10

6 - Giles Farnaby 1560 - 1640

Wooddy-Cock (3) - 6’43

7 - Orlando Gibbons 1583 -1625

Pavana (1) - 2’46

8 - William Byrd

The Woods so Wild (2) - 3’55

9 - Martin Peerson c1571 - 1651

The Fall of the Leafe (1) - 1’56

10 - Thomas Tomkins 1572 - 1656

Barafostus Dreame (2) - 5’35

11 - William Byrd

The Queenes Alman (1) - 3’03

12 - Ferdinando Richardson c1558 – 1618

Pavana-Variation (2) - 4’41

13 - Ferdinando Richardson

Galliarda-Variation (2) - 3’13

14 - John Bull c1562 - 1628

Walsingham (3) - 16’05