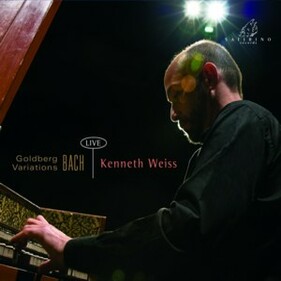

Satirino records · Bach - Goldberg Variations

Goldberg Variations - BWV 988

Kenneth Weiss harpsichord

Satirino records SR091 - released on 23rd April 2009

Recorded live on the 12th October 2008 at the Théâtre St Louis, Pau, France, in the chamber music series of the Orchestre de Pau Pays de Béarn, Fayçal Karoui & Frédéric Morando

Harpsichord

Copy of an anonymous French instrument from the late 17th Century by Philippe Humeau made in Barbaste in 1977, and 'ravalée' in 2006

Tuning

Philippe Humeau

Sound engineer, producer, editing, mastering

Jiri Heger

Design

le monde est petit

Images

© Arthur Forjonel

Thanks to

Frédéric Morando & la Ville de Pau, Jiri Heger, Philippe Humeau, Arthur Forjonel & Supercloclo

Press reviews

The Harpsichord Adventurer -

the American musician’s captivatingly lyrical live recording.

![]()

‘Kenneth Weiss dresses Bach’s music in a vocal coat of arms – mordants, ‘coulés’, trills – of amazonian profusion. This triumphant lyricism, at no stage overdone, places this new version at the top of the list of recent Goldberg Variation recordings.’

Gilles Macassar - Télérama, 16 May 2009![]()

Kenneth Weiss performs Bach

'The reason I'm recommending this positively solar recording today, at the start of the summer, is that it transforms a wonderful lanscape in such a way that we cannot avoid rediscovering it'.

Mathias Heizmann - arte.tv, 7 July 2009

Liner note

by Augustin Le Coutour, translated by Denis Mahaffey

Deutsche Übersetzung hier

Aria with diverse variations for harpsichord with two manuals, known as the “Goldberg variations”, BWV 988.

The fourth part of the Clavierübung, published in 1742 and known as the Goldberg Variations, is, like the Art of the fugue or the two volumes of the Well-tempered Clavier, one of the vast, coherent works in which Bach makes use of his whole systematic cast of mind and all the inventiveness at his disposal. Combining intimacy with virtuosity, it also brings together a degree of conception and scoring that has seldom been equalled.

Legend has it that Bach was commissioned by Count von Keyserlingk, Russian ambassador to the Court of Dresden, to compose a set of variations for the harpsichord, so that a young harpsichordist in his employ and a pupil of Bach, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, could play them in an antechamber next to his bedroom when he could not sleep. The truth of this story has been questioned, even if the talk of insomnia does convey some truth about the Variations. The circumstances of their composition were far more political. Bach began work on them before 1736, at a time when he was seeking the position of "Composer to the Royal Court chapel” in Dresden. He managed to obtain the post the same year, with Keyserlingk’s support. The Variations, presented to the ambassador six years later, are his way of acknowledging the favour, and they also pay tribute in passing to the Prince Elector: many of the variations use the model of the “French suite” a firm favourite with the Prince, and even occasionally recall the rhythm and characteristics of a polonaise, for the Prince Elector of Saxony was also King of Poland.

The work consists of an aria and thirty variations on it. The aria, taken from the Anna Magdalena Notebook of 1725 (Bach adheres to the principle that nothing is created from nowhere), is a sort of saraband in the French style, serene, carried through confidently, and skilfully ornamented. Its symmetrical structure, in two parts with a reprise, ranges from the tonic (G) to the dominant (D) in the first part, returning from dominant to tonic in the second. This pyramidal structure is both simple and powerful. The compelling harmonic pattern forms the hard core of the thirty variations; indeed it is the only way of imparting unity and consistency to a set of variations where each variation is otherwise very much self-contained. This construction is what may be perceived from one variation to the next, although it is no good looking for any figurative relationship to the aria or any complex extension of its melody: the pattern is there, but the theme remains invisible. The thirty variations are arranged in ten groups of three, each such trio comprising a “free” variation (frequently of a dance-like character), then a virtuoso piece (often using both manuels of the harpsichord) and finally a canon (at the unison, then at the second, the third, and so on up to one at the ninth). The whole work is scored in three parts, which help highlight the contrapuntal density of the variations. It is not possible here to dwell on each variation, although it would be well worth doing, but an attentive listener will be aware of all the allusions, genres and moods, from the expressive Italian adagio to the French overture in the Versailles style, and from the theme of a popular song to the most academic canon and counterpoint, sometimes one on top of the other.

The power and vast scale of the work therefore contrast with its very simple principle. Using an air of disconcerting structural simplicity, Bach illustrates Goethe’s dictum that “every constraint contains the promise of a new freedom”. Although little is known about the personality of Johann Sebastian Bach, our most reliable source here, his actual music, shows us that he was disciplined, determined, imbued with a strongly systematic and logical turn of mind, but at the same time displayed enormous inventiveness and freedom of spirit.

Finally, Bach’s music is never completely secular: there is always a clear religious dimension. Read on this level, the Variations are simultaneously a meditation on the one and the many, reminiscent of meditating on the mystery of the Trinity; an exploration of the depth and hidden richness of a base material, similar to meditation on a scriptural text; and finally, to turn to an image widespread in German Baroque poetry, a journey by the soul on the stormy seas of fleeting passions, moods and desires, before returning to port, represented by the tranquil final repetition of the aria from which we started. So, since they do not have a proper title, could we not depart from common usage and call them the “Goldberg meditations” ?

Clavier Ubung bestehend in einer ARIA mit verschiedenen Veraenderungen vors Clavicimbal mit 2 Manualen: “Goldberg-Variationen”, BWV 988

Der vierte Teil der Clavierübung, 1742 herausgegeben und unter dem Titel Goldberg-Variationen bekannt, ist, ebenso wie die Kunst der Fuge oder die beiden Teile des Wohltemperierten Klaviers, einer jener riesigen Werke-Zyklen Bachs, die er mit seinem Sinn für Systematik und seinen geballten schöpferischen Kräften konzipierte. Nicht nur wird in diesem Werk das Intime mit Virtuosität kombiniert, sondern es befinden sich auch Konzeption und Anlage auf derart hohem Niveau, wie es nur selten erreicht wird.

Der Legende zufolge soll der russische Gesandte am Dresdener Hof, Graf von Keyserlingk, Bach damit beauftragt haben, Variationen für Cembalo zu komponieren, die Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, ein junger Cembalist, der in seinem Dienste stand und gleichzeitig ein Schüler Bachs war, in einer Kammer neben dem Schlafzimmer des Grafen spielen sollte, wenn dieser nicht schlafen konnte. Es ist unklar, wie viel Wahrheit in dieser Geschichte steckt, selbst wenn das Element der Schlaflosigkeit im Zusammenhang mit den Variationen durchaus ernstzunehmen ist. Ihre Entstehungsgeschichte hat jedoch eher politische Beweggründe. Bach hatte bereits vor 1736 mit der Arbeit an dem Werk begonnen – dies war zu einer Zeit, als er sich um die Stelle des „Hofcompositeurs“ in Dresden bemühte. Noch im selben Jahr wurde ihm der Titel mit der Hilfe seines Fürsprechers Keyserlingk zuerkannt. Die Variationen, die dem Gesandten sechs Jahre später überreicht wurden, drückten Bachs Dank aus und zollten gleichzeitig dem Kurfürsten Tribut: einer ganzen Reihe von Variationen liegt das Schema der „Französischen Suite“ zugrunde, die der Fürst besonders mochte, und in manchen wird sogar auf den Rhythmus und die Charakteristika der Polonaise angespielt – der sächsische Kurfürst war gleichzeitig König von Polen.

Das Werk besteht aus einer Aria mit dreißig Variationen. Die Aria stammt aus dem Clavierbüchlein der Anna Magdalena Bach von 1725 (Bach hält an seinem Grundsatz fest, dass nichts aus dem Nichts entsteht) und ist eine Art Sarabande im französischen Stil; ruhig, souverän geführt und kunstvoll ornamentiert. Sie ist symmetrisch angelegt, zweiteilig mit Reprise, und bewegt sich im ersten Teil von der Tonika (G-Dur) zur Dominante (D-Dur) und kehrt im zweiten Teil von der Dominante zur Tonika zurück. Diese pyramidenartige Struktur ist sowohl schlicht als auch wirkungsvoll. Die ausdrucksstarke harmonische Anlage bildet den Kern der dreißig Variationen und ist jenes Element, das in dem Zyklus, wo die einzelnen Variationen sonst unabhängig voneinander sind, für Einheitlichkeit und Zusammenhang sorgt. Diese Konstruktion ist von Variation zu Variation wahrnehmbar, obwohl es sinnlos wäre, figurative Beziehungen zu der Aria herstellen oder eine komplexe Weiterführung ihrer Melodie finden zu wollen: zwar ist die Anlage da, doch bleibt das Thema unsichtbar. Die dreißig Variationen sind in zehn Dreiergruppen angeordnet, wobei in jedem solchen Trio eine „freie“ Variation (oft mit tänzerischem Charakter), dann ein virtuoses Stück (in dem meist beide Manuale des Cembalos zum Einsatz kommen) und schließlich ein Kanon (zunächst ein Einklangskanon, dann ein Sekundkanon, dann ein Terzkanon und so weiter bis zum Nonenkanon) vorkommt. Das Werk insgesamt ist dreistimmig angelegt, was die kontrapunktische Dichte der Variationen noch unterstreicht. Es ist hier nicht möglich, auf jede Variation einzeln einzugehen, obwohl das natürlich lohnenswert wäre, doch wird der aufmerksame Hörer die diversen Anspielungen, Genres und Stimmungslagen wahrnehmen – vom ausdruckvollen italienischen Adagio zur französischen Ouvertüre im Versailler Stil und vom Thema eines Volkslieds zu einer besonders akademischen Fuge, wobei die Letzteren manchmal sogar gleichzeitig erscheinen.

Das Werk ist ebenso kraftvoll und riesig in seiner Anlage wie es schlicht von seinem Ausgangspunkt her ist – und mit dieser fast beunruhigenden strukturellen Unscheinbarkeit illustriert Bach Goethes Diktum: „In der Beschränkung zeigt sich erst der Meister / Und das Gesetz nur kann uns Freiheit geben”. Obwohl wir nur wenig über Bachs Persönlichkeit wissen, demonstriert unsere zuverlässigste Quelle – seine Musik –, dass er diszipliniert und zielstrebig gewesen sein und eine ausgeprägt systematische und logische Denkweise gehabt haben muss, doch gleichzeitig eine enorme Erfindungsgabe und innerliche Freiheit besaß.

Letztendlich ist Bachs Musik nie nur weltlich; es ist immer auch eine deutliche religiöse Dimension erkennbar. Wenn man von dieser Ebene ausgeht, so erscheinen die Variationen gleichzeitig als Meditation über das Eine und das Vielfältige, was auf die Meditation des Geheimnisses der Dreieinigkeit hindeutet, ein Erforschen der Tiefe und der versteckten Reichhaltigkeit des Ausgangsmaterials – ähnlich einer Auseinandersetzung mit Bibeltexten – und schließlich, um eine verbreitete Metapher der deutschen Barockdichtung aufzunehmen, eine Reise der Seele über den Ozean verschiedener Leidenschaften, Stimmungen und Wünsche, bevor sie wieder in den Hafen zurückkehrt, der durch die friedvolle Wiederholung der Aria dargestellt wird, die wir zu Anfang hörten. Da sie keinen richtigen Titel haben, könnten wir uns nicht von der Konvention abwenden und sie „Goldberg-Meditationen“ nennen?

Übersetzung Viola Scheffel

Track list

1. Aria

2. Variatio 1 a 1 clav.

3. Variatio 2 a 1 clav.

4. Variatio 3 Canone all’unisono

5. Variatio 4 a 1 clav.

6. Variatio 5 a 1 ovvoro 2 clav.

7. Variatio 6 Canone alla Seconda

8. Variatio 7 a 1 ovvoro 2 clav.

9. Variatio 8 a 2 clav.

10. Variatio 9 Canone alla Terza a 1 clav.

11. Variatio 10 Fughetta a 1 clav.

12. Variatio 11 a 2 clav.

13. Variatio 12 Canone alla Quarta in moto contrario

14. Variatio 13 a 2 clav.

15. Variatio 14 a 2 clav.

16. Variatio 15 Canone a la Quinta in moto contrario a 1 clav., Andante

17. Variatio 16 Ouverture a 1 clav.

18. Variatio 17 a 2 clav.

19. Variatio 18 Canone alla Sesta a 1 clav.

20. Variatio 19 a 1 clav.

21. Variatio 20 a 2 clav.

22. Variatio 21 Canone alla Settima

23. Variatio 22 Alla breve a 1 clav.

24. Variatio 23 a 2 clav.

25. Variatio 24 Canone all’Ottava a 1 clav.

26. Variatio 25 a 2 clav.

27. Variatio 26 a 2 clav.

28. Variatio 27 Canone alla Nona

29. Variatio 28 a 2 clav.

30. Variatio 29 a 1 ovvoro 2 clav.

31. Variatio 30 Quodlibet a 1 clav.

32. Aria

Total CD 77'54