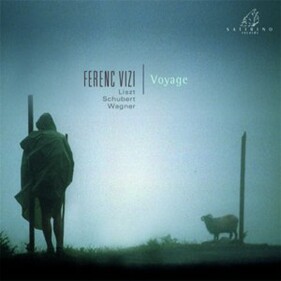

Satirino records · Voyage - Liszt, Schubert, Wagner

Schubert - Fantasia for piano in C major, 'Wanderer', D. 760

Schubert / Liszt - Der Doppelganger (Schwanengesang)

Liszt - 'Après une lecture de Dante', Fantasia quasi Sonata (Années de pèlerinage, 2e année : Italie)

Wagner / Liszt - Ouverture de Tannhäuser

Schubert / Liszt - Die Nebensonnen (Winterreise)

Ferenc Vizi piano

Satirino records SR071 - released on 5th November 2007

Recorded at

Théâtre de Cambrai, France, 27-29 vi 2007

Piano

Steinway

Sound engineer, producer, editing, mastering

Jiri Heger

Design

le monde est petit

Image

© GOUPY DIDIER/CORBIS SYGMA

Translations

Joël Surleau, Boris Kehrmann, Richard Langham Smith, English translation of Dante by James Ford, Prebendary of Exeter, in the metre of the original, London 1865

Thanks to

Françoise Thinat, Georges Gara et le Festival Juventus, Joël Jobé, Marc Chauchard, Jiri Heger, Alain Dessaigne, directeur du Théâtre de Cambrai, Armel & son équipe, Aline Poté & Supercloclo

À la pianiste Françoise Thinat, au poète Lorand Gaspar

comme un témoignage de profonde et affectueuse reconnaissance

It might seem a little hackneyed to entitle this programme ‘voyage’, but it is apparent from every one of the titles that each has an undeniable connotation of travel. And what richness, what deep undertones this idea had in the nineteenth century!

Voyage calls to mind the ‘Wanderer’ of Schubert’s Fantasy; Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister (a work close to my heart); and Dante and Tannhäuser all fulfil their journeys of initiation, born of a necessity which becomes existential even, not, or not only, in reply to a call but in response to an inner thirst for wandering born of confronting destiny: ‘Where you are not, that’s where fulfilment lies!’ confesses the poet Schmidt von Lübeck.

But despite the epic, dramatic and descriptive elements in this music, I prefer to think of this more than anything as an inner voyage, a mystic quest in search of answers to questions one does not even know, posed by an imaginary being, their hand gently raised, questioning, their gaze raised, despite themselves, towards heaven. In that moment, in that gaze, I imagined the trajectory of my programme as an Opera in five acts.

The seed from which it springs is the tumultuous Wanderer Fantasy with its incredible contrasts; its play of darkness and light prolonged, in the Second Act, by a descent into a static abyss whose anguish is overpowering and hypnotic.

Escape is found in the Third and Fourth acts with Dante and Tannhäuser whom I see as complementary to each other, one trying to overcome the desolation of hell; the other to recapture paradise lost, each obsessed with the loneliness of personal destiny and raising up to the point of paroxysm a monumental fresco of the human condition, wrestling with questions of metaphysics and religion: the soul’s salute, Redemption and a divine pardon achieved only by the sacrifice of the eternal beloved.

The last act is a sort of epilogue, the more touching because it comes after this apocalyptic procession of events, as if the voice of the poet, affirmative and free of all sentimentality, shines through, without hardly uttering, or speaking even, its message of peace and consolation, a heavenly serenity stolen from a dream: it is the voice of Schubert ...

Ferenc Vizi

Translation - Richard Langham Smith

Liner Note

There could be no more suitable point of departure for an exploration of Liszt, Schubert and Wagner than the Wanderer Fantasy. It was the most virtuosic piano piece Schubert wrote and was beyond his own not insignificant piano technique. Once, while playing the piece to friends, the composer lost his way in the final section and leapt to his feet: ‘Let the Devil play the stuff!’ he shouted. But it was less the virtuosic aspect that appealed to Liszt, himself unparalleled in fioriture, filigree and fireworks: rather was it the form. Schubert’s Fantasy is like no other piece he ever wrote, a unique outpouring of the young man (he was 25 when he wrote it): it is essentially monothematic. All of its elements (several of them lyrical melodies) are derived from the same series of notes which alter and extend in different ways, change their keys and modality, and appear in different rhythms. It was this metamorphosis of a theme into many variants which Liszt most admired in the Wanderer, and which also became the essence of the leitmotivic procedures of his hero Richard Wagner. Liszt arranged, edited and transcribed the Wanderer. One version he arranged for piano and orchestra, but in another, contained in his edition of Schubert Sonatas, he was the model musicologist, presenting exactly the notes that Schubert had written; adding nothing of his own except some expression marks which he rigorously distinguished as his personal additions.

Liszt’s biographer Alan Walker discusses the composer’s modelling of techniques of thematic transformation from Beethoven, Weber and Schubert. He describes Liszt’s technique nicely. ‘Basic ideas are plunged into the creative fire and emerge transfigured, donning and doffing their disguises along the way’. He identifies Schubert’s Wanderer as the one work above all others from which Liszt perfected his own techniques of thematic metamorphosis.

But Schubert’s appeal to Liszt was not confined to the realm of form and structure. On another level there was Schubert the great lyricist, the tunesmith whose gift for creating memorable, poetic melodies seemed limitless. And although Liszt was also drawn towards more Italianate music, Schubert’s melodies provided a model and a sensibility closer to home. His arrangements of Schubert’s songs (unlike Rachmaninov’s for example) respect Schubert’s original harmonies, though he at times adorns the melodies with all kinds of garlands. And we should remember that Schubert—maybe above Beethoven—was a master of harmonic invention, particularly in the realms of chromatic harmony and in a constant veering between major and minor. His love of juxtaposing keys at the relationship of a third was also an element taken over by Liszt whose own stretching of the possibilities of tonal harmony almost strayed into atonality in his last pieces.

Above all, we know that Liszt, a deeply literary man, was fascinated by Schubert’s alliance of music with poetry. He disapproved of the first editions made of his Schubert song transcriptions because the words of the poetry were printed separately from the music: his idea, realised only in subsequent editions, was that the words be printed on the piano part, exactly allied to each note of the melody as in the original song. In his early years with Marie, Liszt’s German was not up to much so she translated the poems into French for him in order that he could exactly match the poetry to Schubert’s settings.

Liszt’s enthusiasm for Schubert had begun in his late teens, partly catalysed by his friendship with a Belgian violinist and composer Chrétien Urhan whose eccentricity seems to have at least equalled that of the composer himself in his later life, and paralleled it in that it was centred on religious fervour (Liszt, we should remember, was a self-styled Abbé). Urhan dressed in a light-blue frock coat, in honour of the Virgin Mary. And although he played in the orchestra of the Paris Opera, he took pains never once in his life to set his eyes upon the stage, lest the devil should appear amongst the scantily clad dancers. But he was a great advocate of Schubert, and introduced his works in Paris within a year of the composer’s death in 1828. Liszt’s first transcriptions of Schubert were made in 1833 when he was in his early twenties and he turned his attentions to further Schubert arrangements until the late 1840s. The two arrangements in this recital both date from 1838–9.

If Schubert was a major literary obsession, the works of two Italian poets, Dante and Petrarch, were equally strong literary passions. A good deal of rose-coloured fantasy surrounds Liszt’s stay in Italy with Marie d’Agoult and early biographies romanticise the couple’s readings of Dante and have Liszt composing the so-called Dante Sonata at Bellagio in 1837, beside an early nineteenth-century statue of the poet leading Beatrice into Paradise. In fact it was not begun until two years after this sojourn. What is clear is that it particularly consumed Liszt who would not venture out during its composition.

The piece closely follows several cantos of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Inhabiting the key of D minor—a traditional key for pieces associated with death, and the key of Liszt’s Totentanz—the piece begins with a dramatic series of tritones to conjure up hell. As Alan Walker has pointed out, a revealing copy of the work in the possession of Liszt’s pupil Walter Bache has pencilled annotations linking the tumultuous first subject of the piece to Canto 3 of the Inferno:

There sighs, and moans, and loud bewailing woe,

Resounded through the dim and starless haze;

The which constrain’d at first my tears to flow.

Discordant tongues, speeches of horrid phrase,

Words of distress, accents of anger sore,

Shrill and hoarse voices, sound of hand with these,

An uproar made, which gather’d more and more

In that eternally dark-tinted air,

Like to the sand, when whirlwinds sweep the shore.

A descending octave passage is linked to canto 34:

“The banners of the Emperor of Hell”

Come streaming towards us; therefore onward gaze,

My Master said, “that thou discern Him well.”

As, when the vapour breathes with thickening haze,

Or when the night embrowns our hemisphere,

Its moving vans a mill from far displays;

So now in front a structure ‘gan appear:

Then sprang I, to escape the whirlwind strong,

Behind my Chief; none other screeen was near. [...]

When in our progress we had reach’d so far,

That thence it pleas’d my Master me to show

The creature, once in Heaven surpassing fair ...

In contrast to the D minor depiction of the satanic, is the beatific vision which takes over as the fires of hell are extinguished. A lyrical melody sings out in the key of F sharp major, for Liszt a paradise key. In fact Liszt has gone back to his model of the Wanderer, for the melody is a thematic transformation of the earlier demonic motive now turned major.

A further literary source is also connected with the piece whose title is borrowed from a poem of the same title from a collection by Victor Hugo entitled Les Voix intérieures, written in 1837. Hugo and Liszt were close friends and their aesthetics overlapped in many ways.

On the subject of Liszt and Wagner much can be written on several levels. Here we need only record Liszt’s constant admiration for a man who might be seen as his rival, if not his victor, in the competition for the composer who most distilled the essence of Romanticism. Liszt had championed Wagner’s music as a conductor and had helped him in times of trouble. His daughter Cosima, bore Wagner two illegitimate daughters and a son (Siegfried) before divorcing her husband von Bulow and marrying Wagner in 1870. Liszt had many times conducted the overture to Tannhäuser and made his piano arrangement of it in 1848. A few quotations from Wagner’s own note on the opera cannot be bettered as an introduction to the mood of this quintessentially Romantic work, none of whose spirit is lost in Liszt’s masterly transcription:

‘The Overture introduces us first to the Pilgrims’ Chorus which rises up and swells to a mighty outpouring and finally passes into the distance. In the twilight there are dying echoses of the chorus. As night falls, magic visions are seen. A rosy mist swirls upwards, sensuously exultant sounds reach our ears and the blurred motions of a fearsomely voluptuous dance are revealed. (At this moment the feverish Allegro of the Overture begins; the harmonics turn chromatic and we hear the first of many bacchanalian themes associated with the unholy revels in the legendary Venusberg.) [...]

Tannhäuser sings his jubilant chant of love. He is answered by wild shouts. The rosy clouds envelop him more closely. Intoxicating fragrances surround him. In a tempting half-light his clairvoyant eyes now behold an indescribably attractive woman’s figure. It is Venus herself who has appeared to him. [...]

Redeemed from the curse of ungodly shame, the Venusberg itself joins its exultant voice to the godly chant. Thus each pulse of life leaps and throbs to the song of salvation., and those dissevered elements, soul and senses, God and nature, are united in the sacred kiss of love.’

Richard Langham Smith

Poetic texts

Dante Alighieri

Inferno, Canto 3

Quivi sospiri, pianti, e alti guai

Risonavan per l’aer senza stelle,

Per ch’io al cominciar ne lagrimai.

Diverse lingue, orribili favelle,

Parole di dolore, accenti d’ira,

Voci alte e fioche, e suon di man con elle,

Facevano un tumulto, il qual s’aggira

Sempre in quell’aria senza tempo tinta,

Come la rena quando il turbo spira.

Inferno, Canto 34

Vexilla Regis prodeunt Inferni

Verso di noi: però dinanzi mira,

Disse il Maestro mio, se tu il discerni.

Come quando una grossa nebbia spira,

O quando l’emisperio nostro annotta

Par da lungi un mulin che al vento gira;

Veder mi parve un tal dificio allotta:

Poi per lo vento mi ristrinsi retro

Al Duca mio; chè non v’era altra grotta. [...]

Quando noi fummo fatti tanto avante,

Ch’al mio Maestro piacque di mostrarmi

La creatura ch’ebbe il bel sembiante ...

Victor Hugo

Après une lecture de Dante

Quand le poète peint l’enfer, il peint sa vie :

Sa vie, ombre qui fuit de spectres poursuivie ;

Forêt mystérieuse où ses pas effrayés

S’égarent à tâtons hors des chemins frayés ;

Noir voyage obstrué de rencontres difformes ;

Spirale aux bords douteux, aux profondeurs énormes,

Dont les cercles hideux vont toujours plus avant

Dans une ombre où se meut l’enfer vague et vivant !

Cette rampe se perd dans la brume indécise ;

Au bas de chaque marche une plainte est assise,

Et l’on y voit passer avec un faible bruit

Des grincements de dents blancs dans la sombre nuit.

Là sont les visions, les rêves, les chimères ;

Les yeux que la douleur change en sources amères,

L’amour, couple enlacé, triste, et toujours brûlant,

Qui dans un tourbillon passe une plaie au flanc ;

Dans un coin la vengeance et la faim, sœurs impies,

Sur un crâne rongé côte à côte accroupies ;

Puis la pâle misère, au sourire appauvri ;

L’ambition, l’orgueil, de soi-même nourri,

Et la luxure immonde, et l’avarice infâme,

Tous les manteaux de plomb dont peut se charger l’âme !

Plus loin, la lâcheté, la peur, la trahison

Offrant des clefs à vendre et goûtant du poison ;

Et puis, plus bas encore, et tout au fond du gouffre,

Le masque grimaçant de la Haine qui souffre !

Oui, c’est bien là la vie, ô poète inspiré,

Et son chemin brumeux d’obstacles encombré.

Mais, pour que rien n’y manque, en cette route étroite

Vous nous montrez toujours debout à votre droite

Le génie au front calme, aux yeux pleins de rayons,

Le Virgile serein qui dit : Continuons !

6 août 1836

Der Doppelgänger (Schwanengesang)

Still ist die Nacht, es ruhen die Gassen,

In diesem Hause wohnte mein Schatz;

Sie hat schon längst die Stadt verlassen,

Doch steht noch das Haus auf demselben Platz.

Da steht auch ein Mensch und starrt in die Höhe,

Und ringt die Hände, vor Schmerzensgewalt;

Mir graust es, wenn ich sein Antlitz sehe -

Der Mond zeigt mir meine eigne Gestalt.

Du Doppelgänger! du bleicher Geselle!

Was äffst du nach mein Liebesleid,

das mich gequält auf dieser Stelle,

So manche Nacht, in alter Zeit?

Heinrich Heine

Die Nebensonnen (Winterreise)

Drei Sonnen sah ich am Himmel steh'n,

Hab' lang und fest sie angeseh'n;

Und sie auch standen da so stier,

Als wollten sie nicht weg von mir.

Ach, meine Sonnen seid ihr nicht!

Schaut Andern doch ins Angesicht!

Ja, neulich hatt' ich auch wohl drei;

Nun sind hinab die besten zwei.

Ging nur die dritt' erst hinterdrein!

Im Dunkeln wird mir wohler sein.

Wilhelm Müller

Track list

Franz Schubert 1797–1828

Fantasia for piano in C major (‘Wanderer’), D. 760 (Op. 15)

1 - Allegro con fuoco ma non troppo [5’42]

2 - Adagio [6’27]

3 - Presto [4’43]

4 - Allegro [3’28]

Schubert - Liszt

5 - Der Doppelganger (Schwanengesang) [4’31]

Franz Liszt 1811–1886

6 - Après une lecture de Dante [16’26]

Fantasia quasi Sonata (Années de pèlerinage, 2e année : Italie)

Wagner - Liszt

7 - Ouverture de Tannhäuser [17’51]

Schubert - Liszt

8 - Die Nebensonnen (Winterreise) [4’51]

Total CD - 64’01

Satirino records is delighted to receive the support of

Mécénat 100%

for the publication of Ferenc Vizi's 'Voyage'.

Mécénat 100% is an association bringing together professionals and small and medium-sized enterprises that gives its support to cultural activities aiming to obtain recognition for artists of exceptional talent.

The originality of Mécénat 100%’s approach lies above all in its method of operation: 100% of the donations received are allocated to artistic projects.

Mécénat 100% has ministerial approval and welcomes new members.

To get in touch with Mécénat 100%, just log into the Internet site www.100-pour-100.org

Jacques Binisti (lawyer),

Christophe Maurin, ACI (auditors),

Cabinet MALEMONT (Industrial Property attorneys),

Gérard Méligne, FrogLog (website designers),

Laurence Chauchard, Henri Peuchot and Jean-Paul Kédinger have sponsored this recording, on behalf of Mécénat 100%.