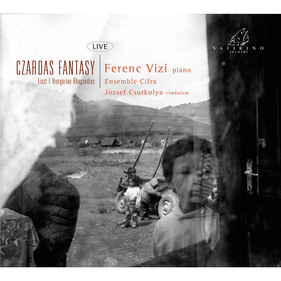

Satirino records · Czardas Fantasy

Liszt - Hungarian Rhapsodies

Hungarian Gypsy Music

Ferenc Vizi piano

Ensemble Cifra

Dezsõ Rontó, prímás (violin)

József Csurkulya senior, cimbalom

Ágoston Bartha, viola & hurdy-gurdy

Róbert Csõgör, double bass

József Csurkulya junior, cimbalom

Satirino records SR131 - released 5th June 2013

Live Recording

Targu-Mures Philharmonic, Romania, 3 xi 2012

Instruments

Piano Yamaha

Tekerő (Hurdy-gurdy) - Mihály Bársony, 1980

Hungarian cimbalom ‘Kozmosz’ - István Jancsó

Sound engineer, producer, editing, mastering

Jiri Heger

Images

Copsa Mica, Romania © Lisa iltse / Corbis

Ferenc Vizi © Arthur Forjonel

Design

le monde est petit

Thanks to

Vasile Cazan, Margit Szallós-Farkas, Jiri Heger, Supercloclo, Aline Pôté, Ludovic & Maria Vizi

This recording is dedicated to my grandfathers, Kovács Mihály and Vizi Ferenc, both deceased, and to Gagyi Belus, a grand gentleman to whom I owe so much, and without whom I would have continued to not know how to play…. the accordion.

My warmest thanks go to the Ensemble Cifra, József Csurkulya senior, Ágoston Bartha, Róbert Csõgör, Dezső Rontó and to my childhood friend, József Csurkulya junior.

Ferenc Vizi

Press reviews

"Après avoir terminé votre goulash, vous continuez par des palincsinta. Au moment où vous entamez ces crêpes sucrées à la hongroise, les musiciens attaquent une rhapsodie de la même origine, signée Liszt mais interprétée couleur locale : piano, violon, vielle à roue et cymbalum, parfum tzigane garanti. Tel est l’esprit de cet enregistrement live qui donne l’impression d’être en pleine campagne hongroise aux confins de la Transylvanie dans une auberge recommandée par le Guide du Routard parce que la musique tzigane fait partie du décor. Ce Liszt-là, en « version originale », traduit plus sûrement les origines et les inspirations du compositeur que les « versions de salon » qu’on a l’habitude d’entendre, ce qui lui donne ce goût étrange venu d’ailleurs. A côté d’œuvres de Liszt, on trouve ici des csardas typiques, c’est-à-dire des musiques populaires destinées à la danse, mélodies vives et brillantes interprétées avec une spontanéité et un côté enjoué qui laissent imaginer que les musiciens les connaissent depuis le berceau." Gérard Pangon, Musikzen , août 2013

"Le pianiste Ferenc Vizi revient aux sources, et in vente une 'interprétation imaginative' qui met en valeur le lien entre le génie de Liszt et la tradition des Tziganes hongrois... C'est du grand art pour tout public. Le piano, sublime, ne cède rien au cymbalum, mais les pièces merveilleuses du soliste virtuose sont portées par l'enthousiasme de l'ensemble Cifra, avec des airs de village à la vieille à roue et le magnifique La grue vole haut dans le ciel, origine de la quatorzième rhapsodie. Liszt peut tendre l'oreille !" Michèle Fizaine, Midi Libre

Liner Notes

I would like to make clear how this programme started, not from an essentially musicological basis...

Certainly, in these Rhapsodies there is a clearly identified influence of the Gypsy music that is so well-known in Hungary - with which I am not unfamiliar, given my origins in Transylvania, now part of Romania, where I lived until I went to study in Paris. So this is not an authentically pure Hungarian music, as would later be shown by the ethno-musicological work of Bartók and Kodály.

I was in fact getting ready to decipher Liszt's 11th Rhapsody, when my eyes fell on an indication right at the start: ‘quasi zimbalon’ - like the cimbalom…

But how did Liszt come into contact with Hungarian Gypsy music? What did he feel the first time he heard it? I imagined something like a film-script, a bit like the musical duel between Liszt and Thalberg in the Princess Belgiojoso's Paris salon in 1837, but this time in a Czarda, a busy country inn where the Gypsies played popular songs and dances every evening.

So we can imagine Liszt sitting at a table in a shadowy corner of a modest inn, while Gypsies play a bit of everything the customers like - typically ‘Czardas’ songs and dances, illustrated in our programme by the ‘Poppy Czardas’ or ‘Aïe Aïe Aïe’ – and the latest hits, drinking songs like ‘Pour Me Some Wine so I Can Forget Her’, romantic songs full of nostalgia like ‘The Old Lime Trees of Buda’ or ‘The Crane Flies High in the Sky’ – a popular Hungarian song that inspired Liszt's 14th Rhapsody. In short, a bit of everything, arranged in their own style. As says Ágoston Bartha, founder of the Cifra group and a folklore enthusiast, these musicians had to make themselves heard above the background noise of the inn, attracting attention by freely alternating rhythms and tempos, with vertiginous accelerations and slow, tearful vibratos, or deliberately maintained metronomic regularity ‘so you could adjust a Swiss watch by the beat’. Like all buskers, they had to captivate, charm, and arouse emotion to keep the customer's attention. And imagine Liszt, who has been listening to them for a while, warmed by the music and the wine, getting up and taking a seat in front of the dusty old piano forgotten on the other side of the room. He breaks in with improvisations inspired by what he has just heard, a jam session develops, a dialogue of joyful duellists that lasts long into the night, that night in a Czarda when Liszt met Gypsy music...

Well, not long ago I came across a note from Debussy, amusingly like my imaginary film script, but this time in a café in Budapest one night in 1910, when he listened to the celebrated Gypsy violinist Béla Radics…

‘... where in a very ordinary café Radics was giving the impression of sitting in the shadow of the forest, searching from the bottom of his soul that special Gypsy melancholy of a heart that aches or laughs, almost in the same moment, but which we so rarely experience. He would draw your secrets out of a locked strong-room. In my opinion, this music should never be altered or adapted. It should be defended, even, if that were possible, from the ham-handed attentions of ‘professionals’. This means you should respect your Gypsies. They should no longer be regarded as simple entertainers summoned for an anniversary or to help you drink your champagne…’

Ferenc Vizi - Translation Richard Maxwell

"Of all the Arts, Instrumental Music is exactly what expresses their feelings without exactly defining them, without clothing them in allegory or the actions of a poem or the conflicts in a play." (Franz Liszt : Des Bohémiens et de leur musique en Hongrie, 1859)

Western music’s taste for the exotic goes back to the seventeenth century. Particularly in Baroque French spectacle the ballets à entrées delighted in the portrayal of exotic peoples: Turks, ‘savages’, all kinds of Indians and even Peruvians. But apart from an extra tinkle of percussion and an occasional unexpected interval, these imports brought no music of their own: the exotics just danced minuets, like everyone else.

Towards the end of eighteenth century, however, a deeper kind of exoticism crept into classical music. At first it was the fashion for Turkish music: the janissary style of music typified by Mozart’s Turkish Rondo and explored in his opera Il seraglio. It was a short-lived fashion which even caused novelty pianos to be equipped with ‘drum and jingle’ pedals to give the impression of an Oriental band. It soon faded in favour of a more fertile ‘other’ music right on its doorstep: that of the gypsies. Their music had a lot more to satiate the taste for the exotic, particularly the music of Hungary with its especially talented violinists, its use of the exotic Cimbalom and its hypnotic dances.

Haydn was one composer who explicitly enlivened his String Quartets with the gypsy style. He was followed by Schubert, several of whose shorter piano pieces are in Hungarian dance rhythms—the famous Moment Musical in F minor for example. Many of his songs also display features from the neighbouring eastern countries: think of his organ-grinder (Der Leiermann) from Winterreise. Less well-known but more extreme is his piano-duet Divertissement à l’hongroise: a compendium of gypsy imitations including stereotypical cimbalom cadences. Here is not the place to extend this catalogue save to mention that at its beginning Hummel and Weber can also be cited, and that at its end, Brahms’s Hungarian Dances are a notable late-flowering of the same genesis.

Among extended studies of European gypsies and their customs, three may be identified as particularly important. The first, by Heinrich Grellmann, originally dated from 1783 but was translated in the nineteenth century and altered in French and English versions. His denigration of gypsies is more than tainted with racism, but he wrote interestingly of their musical prowess in the English edition: ‘Music is the only science in which the Gypsies participate, in any considerable degree; they compose likewise, but it is after the manner of the Eastern people, extempore’. This spontaneity was to be one of the over-arching features of their music-making which attracted Classical composers in danger of becoming trapped in the strait-jacket forms which their own music had evolved—the dance forms; the Sonata, the Rondo and the set of Variations. Only looser concepts such as the Fantasia, Divertissement and Rhapsody could release them.

The second writer on gypsies was an English Minister of Religion, George Borrow. He lived with them in Spain and dispelled many of Grellmann’s negative remarks. His highly influential work was published in French in the 1840s just before Prosper Mérimée wrote his highly successful Carmen on which Bizet based his opera of 1875. The third study was an erudite book by Franz Liszt himself, originally intended as a commentary on his Rhapsodies Hongroises which dated from the 1850s, but vastly expanded and first published in 1859. It was several times reprinted and translated into English. Although it confuses Gypsy music with Hungarian folk music (which had become confused anyway), and although much of it may have been ghosted by his lover of the time, the Princess Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein, it remains a treasure house of commentary on his capturing of the style hongrois in the Rhapsodies and in particular his dissection of the essential expressive elements of this style. Liszt himself commented on his concept of the Rhapsodie:

By the word Rhapsodie we wanted to highlight its fantastically ‘epic’ quality. Each one of them is a part of a cycle of poetry, remarkable for the unity of its inspiration which is above all ‘national’, coming from one race and portraying their soul and their intimate feelings nowhere more expressed than in their own particular forms, invented and practised by them alone.

Although it may sound facile as an assertion, there are essentially two elements to the style hongrois: slow and fast. Liszt puts it like this: ‘The gypsy musician searches for an art-form which expresses the most desolate sadness and the most passionate, unstoppable joy’. The first style is known as hallgató, meaning music to be listened to rather than danced to. Hallgató is its highly expressive, dependent on the meaning of the song being interpreted. It is through the improvised embellishment with which Liszt’s ideal musician imbues his song that its full expression is realised. He explains, ‘The master who is most to be admired is he who enriches his theme with such a profusion of traits - appoggiaturas, tremolos, scale, arpeggios and diatonic or chromatic passages [...] that under this luxuriant embroidery the primitive thought is no less visible than the material of his sleeve under his houppelande.’ We are not so very far away from the profound song tradition of Southern Spain, the Cante jondo—deep song—of the Andalusian gypsies. Except that nobody sings.

As far as the dance-styles are concerned, the most typical variety became known as the verbunkos, a term which originally designated a jolly type of music employed for luring young men into the military. Liszt calls this second characteristic the Frischka ‘in very quick time which suddenly or quickly gets faster’. A particular feature was the gradual acceleration of dances which began slowly: we may think of the Gypsy Song (Chanson bohème) which opens the second act of Carmen. Still surviving to this day is the celebrated Czardas which embodies both slow and quick sections: several of Liszt’s Fantasies follow this model. Liszt best expressed its gypsy roots as ‘The love of gaiety, of dancing, of music, of women, of drunkenness, of orgies, of reuniting [...] these are their joys ....’

Liszt’s Rhapsodies imitate Hungarian music in several ways: n°11 is explicit in indicating that the whole opening section is to be quasi zimbalo—in imitation of a cimbalom, and marked Lento a capriccio, it is clearly in the hesitant, rubato style we have identified as hallgató. The present recording demonstrates this uniquely.

Imitation of the instrumental idiosyncrasies of Hungarian and gypsy styles had been established long before Liszt but no one before him had extended them in such a virtuosic manner. Ubiquitous in the society cafés of middle-European cities, the violinists of the gypsy bands entertained fashionable clients with ever-increasing clever tricks, most notably with fleeting scales, bowings and arpeggios rising to unparalleled heights, and also leaps between strings. Haydn and Schubert, among others, had exploited this aspect, in the latter case transferring the style to the piano but hardly as dexterously as Liszt does in the Pesther Carneval (n°9) in which the various dances are separated by seemingly aimless, filigree lines, highlighting the pianist’s delicacy of touch and timing. Beginning rhapsodically in hallgató style, it presents its first theme capriccio soon to be taken up in another typical style where the whole melody is sounded in parallel thirds, a typical feature of cimbalom playing where neither the lower nor upper note of the third was considered predominant: both were integral.

Other features of Cimbalom playing are used in the Introduction to n°7: the presentation of the melody with acciaccaturas; the typical tremoli interspersed; and a more pronounced exploitation of the ‘melody in thirds’ formula. The turning ornaments and cadential patterns are also formulaic. Here gypsy dances (the first is marked Allegro zingarese—‘a gypsy Allegro’) are sandwiched between more expressive sections which use a harmonic technique also associated with the ‘Hungarian / Gypsy’ style: the use of diminished chords based on minor scales with a sharpened fourth (once again we may think of Carmen, who has a motive on a similar scale to identify her as a gypsy.) Extraordinary virtuosity is also employed—as so often in these pieces—to ensure the piece concludes at maximum voltage.

The rendering of n°s 14, 10 and 11 introduces a sparing use of the folk instruments. In n°14 in which a Funeral March is interspersed with a rendering of a Hungarian popular song ‘The Crane Flies High in the Sky’ played on the violin and cimbalom. The juxtaposition gives us a unique opportunity to hear the links between real Hungarian music and his 1850s Rhapsodies: Liszt has already confirmed this in his book, so here the folk instruments return to join in the last dance, interspersed with a thoughtful passage of duetting between piano and cimbalom.

We may reflect upon the word ‘authenticity’, a term over-used in relation to performances which can be rather dry. Surely an imaginative juxtaposition of a modern-day interpretation which brings out the connections between Liszt’s virtuosic genius and the music which inspired him touches a vein of the ‘authentic’ which no entirely historical performance could hope to penetrate. And it’s a tribute to the Hungarian in Liszt who, although he lived most of his life abroad, returned increasingly to his homeland in later life, and in whom—whether real or not—the gypsy spirit was never far from the surface.

Ágoston Bartha on Hungarian gypsy music

Poppy Czardas

I'm a founder member of the Cifra Ensemble, where I play the viola and the hurdy-gurdy, and I have a very large collection of archive recordings of Hungarian Gypsy music. It was on an old and unique recording of Józsi Vidák and his orchestra Gödöllő, very well-known in Hungary, that we found the piece by Frigyes Szalay, the ‘Poppy Czardas’.

Aïe, Aïe, Aïe

This traditional piece of Romanian Gypsy music is played with a regularly accelerating rhythm. As Gypsy dances are noisy affairs the musician is obliged to push his instrument to its limits. In fact without amplification a difficult to hear orchestra quickly becomes unsustainable, because it gets no bookings. In addition to the violin virtuoso, the cimbalom player is very important, and this instrument, played solo or as part of the accompaniment, gives Romanian and Hungarian folk music its typical character. In this number you can hear the cimbalom played by József Csurkulya in both roles.

The Old Lime Trees of Buda

Franz Liszt could never have heard this song, created in 1958 in Budapest for the operetta Bástyasétány 77 (77, Rampart Street) by Mihály Eisemann. But we chose it for its delicate melody, which is a very close equivalent of the soul and sentiments of Liszt's time. And stylistically it could well have been composed at that period. What's more, since the operetta was written, ‘The Old Lime Trees of Buda’ has been part of the repertoire of all Hungarian Gypsy orchestras.

Hungarian Czardas for Hurdy-gurdy

In this piece you can hear the hurdy-gurdy, a monophonic folk instrument very popular in Hungary, in all its splendour and multiple rhythmic possibilities. This instrument was made in 1980 by Mihály Bársony, the last traditional Hungarian instrument maker. I was myself apprenticed to him, and he played the hurdy-gurdy marvellously well. This Hungarian czardas and its improvised ornamentations is an authentic example of Hungarian folk music.

Cimbalom solo from the village of Magyarpéterlaki in Transylvania

This superb folk dance from his native village of Magyarpéterlaki begins with a solo by József Csurkulya. This is the music that is danced to at marriages, dances and other festivities. Several guests may take part and only an orchestra with a powerful output can make itself heard, and the musicians adapt their instruments to achieve this. For example, the three-stringed viola that you can hear here provides the rhythmic accompaniment on all three strings simultaneously, using a flattened bridge so that three note chords can be played throughout.

Pour Me Some Wine

This is a typical czardas, one could say emblematic of music played by Gypsy orchestras. The song finishes with a fast movement that accelerates progressively. Similar czardas can be classified by their composers. They are often authentic Hungarian folksongs. The czardas was originally a dance accompaniment, but in our time, with captive concert audiences, the development of improvisation, ornamentation and rhythmic freedom, has found freer expression.

The Crane Flies High in the Sky

This pretty traditional melody is the leitmotif of Franz Liszt's 14th Rhapsody. The accompanying song, ‘The Crane Flies High in the Sky’ is found on numerous archive recordings made in the early 1900s. Liszt certainly heard it before he wrote the Rhapsody.

Translation Richard Maxwell

József Csurkulya

József Csurkulya junior (cimbalom), was born in 1974 in Marosvásárhely near Targu-Mures in Transylvanian Romania. His family is a cimbalom dynasty. At the age of 8 he started to play in the Hungarian State Folk Ensemble in Targu-Mures and after studying percussion at the conservatory there went on to perform with the Targu-Mures State Philharmonic Orchestra. When his family moved to Budapest he studied cimbalom making and performance at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music where he graduated and soon started to teach cimbalom and chamber music. Since 2000 he has been playing traditional Hungarian, Balkan and Near-Eastern music, as well as electronic music and jazz with ’Besh o droM’ - www.beshodrom.hu

Ensemble Cifra

Dezsõ Rontó - prímás (first violin), was born in 1963 into a family of gypsy musicians in Miskolc. His brothers Róbert and Attila are also professional musicians. Dezsõ started learning the violin at the age of 7 and later studied at the town conservatory. In 1980, he became the first of the ‘prímás’ of the Rajkó Orchestra in Miskolc. In 1986, he was a founding member of the 100 Violin Gypsy Orchestra. In 2001, he was winner of the famous Budapest ‘prímás’ competition. Since the age of 20 he has been playing with gypsy orchestras throughout Europe and in the USA.

József Csurkulya senior - cimbalom, was born in 1944 in Magyarpéterlaka, Transylvania. He started playing the cimbalom with his family at a very early age. By the age of 14 he was performing with the ensemble Maros in Transylvania. As well as his activities as a musician, he dedicates himself to restoring and building cimbaloms and is also a master of string making.

Ágoston Bartha - viola & hurdy-gurdy, was born in 1956 in Budapest. It was in the 1970s that he started to be interested in traditional music. Since then he has become viola and hurdy-gurdy player in several ensembles and as of 1990 has been leader of the ensemble Cifra, happily returning to the free, itinerant life of travelling musicians. He has produced the ensemble's recordings since 1997 and collects pre-war 78 LPs of Hungarian gypsy music, of which he is proud to have one of the most important collections.

Róbert Csõgör - double bass, was born in 1966. He studied cello at music school and became a proficient performer of traditional music at a very early age. He has gone on to play with several ensembles playing alternatively violin, three string viola and double bass.

Track list

1 - Rhapsody N°11 - S. 244/11 in A minor - 6’11

Piano & Ensemble Cifra

2 - Rhapsody N°10 Preludio - S.224/10 in E major - 5’15

Piano & Cimbalom

3 - ‘Poppy Czardas’ - 3’37

Ensemble Cifra

4 - ‘Aïe, Aïe, Aïe’ - Gypsy Czardas - 3’23

Ensemble Cifra

5 - Rhapsody N°12 - S.244/12 in C sharp minor - 9’13

Piano

6 - ‘The Old Lime Trees of Buda’ - 2’55

Ensemble Cifra

7 - Hungarian Czardas for Hurdy-gurdy - 2’53

Ensemble Cifra

8 - Rhapsody N°9 Pesther Carneval - S.244/9 in E flat major - 10’40

Piano

9 - Cimbalom solo from the village of Magyarpéterlaki, Transylvania - 5’19

Cimbalom & Ensemble Cifra

10 - ‘Pour Me Some Wine’ - 4’31

Ensemble Cifra

11 - Rhapsody N°14 Hungarian Fantasy - S.244/14 in F minor & ‘The Crane Flies High in the Sky’ - 14’42

Piano & Ensemble Cifra

Total CD 68’46