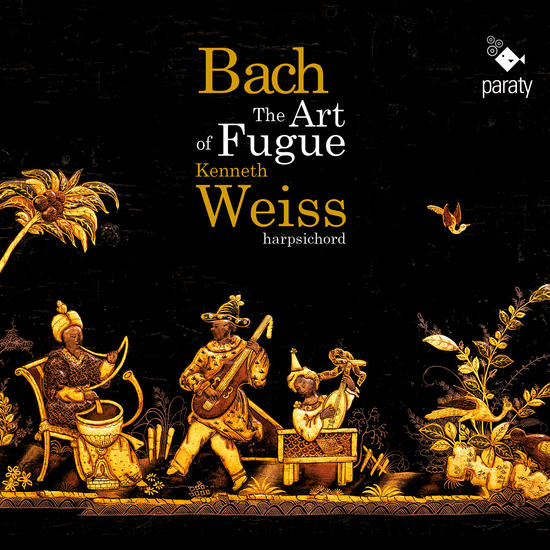

Satirino records · The Art of Fugue

J. S. Bach, 1685-1750

The Art of Fugue - BWV 1080

Kenneth Weiss harpsichord

In collaboration with Satirino

Paraty 1221.1115 - released 25th February 2022

Recorded on the 1782 Taskin harpsichord belonging to the Museu Nacional da Música at the Centro Cultural de Belém, Portugal

© Nuno Ferreira Santos

Producer

Bruno Procopio

Sound and master editing

Hugo Romano Guimarães

Artistic direction Hugo Romano Guimarães

Graphic design

Antoine Vivier

Translation

Christine Menguy

Photography

© Museu Nacional da Música (cover), © Nuno Ferreira Santos (booklet cover), © Jenny Gorman (p.11)

Recording

Centro Cultural de Belém, Portugal, 16 & 17/5/2021

Harpsichord

Pascal Taskin, 1782, Paris, Museu Nacional da Música, Inv. MNM 1096, Lisboa, Portugal

Tuning

Geert Karman

Paraty Productions

contact@paraty.fr www.paraty.fr

Acknowledgements

Graça Mendes Pinto and Helena Miranda at the Museu Nacional da Música, Paula Fonseca and Inês Correia at the Centro Cultural de Belém, and Hugo Romano Guimarães. Special thanks to Geert Karman, without whose help and support this recording would not have been possible.

Co-produced with the Museu Nacional da Música in collaboration with the Centro Cultural de Belém, Portugal

Press reviews

"Accomplishing a veritable tour de force, Weiss unfurls the Art of Fugue like a story... full of passion yet never at the expense of a rigorous deployment of the voices. The mastery of structure is amplified by the life-giving impetus that runs through it... this Art of Fugue by Kenneth Weiss, through its clarity of ideas, its deep commitment and sensitivity, earns a position among the work's recording pinnacles."

Jean-Christophe Pucek, Diapason, March 2023

The Art of Fugue by Kenneth Weiss : poetry and serenity

"…(Kenneth Weiss) allows the score to breathe… thanks to his expressive phrasing and mastery of tempo… never blurring the musical narrative. His flesh and soul performance reveals the extent to which Bach’s cerebral constructions also speak to the heart. It’s for this reason that we are warmly recommending this recording to those who might be put off by the work’s austere reputation, and who wish to discover the profound humanity of the Art of Fugue."

Christophe Steyne, Crescendo Magazine, 25th July 2022

“Kenneth Weiss's interpretation is so wonderfully natural that one ceases to think of the performer and focuses entirely on the uninterrupted hypnotic flow of this contrapuntal apotheosis. However, to achieve all this, Weiss deploys his considerable technical resources, his mastery of tempo and rhythm, of articulation, the coordination between the two keyboards and the clarity of the polyphony, attaining a dimension that is both profound and natural. Although Weiss places great value on the sobriety of his teacher, Leonhardt, he far surpasses him in technique and musicality.”

Manuel de Lara Ruiz, Scherzo, May 2022

'A new Art of Fugue recording that is remarkable for its unsurpassed virtuosity and expressive finesse. The mastery and depth of the New York harpsichordist Kenneth Weiss is totally compelling. His previous Bach recordings revealed his supple and often radiant temperament… drawing on his resonant technical abilities and above all creating his own intimate, poetical journey.'

Liner note

Although familiar with the Art of Fugue for much of my life, I did not set about learning it in its entirety until 2020. When Covid-19 put all concert life on hold, like my fellow musicians, I was left homebound with an ever increasing calendar of cancellations; my first Art of Fugue recital was the one I mourned the most. I took advantage of the time of seclusion to immerse myself in the work. Day after day, I turned to it for comfort, for inspiration and for connection in an unsure world. To be in constant awe at Bach’s limitless imagination and skill while challenging myself to hear - really hear - all that was going on, elevated my mood and gave me great joy. It was an act of devotion. I cherish the memory of it.

In 2019, I had the good fortune to be asked by the Museu Nacional da Música to play the inauguration concert on their newly restored historic Taskin harpsichord. I was instantly captured by its depth of sound, strong yet sweet. It was a magical feeling - knowing that my hands were making the instrument sing again, as other hands have done on the same beautiful keyboard for over two hundred years. I am indebted to the Museu for making it possible for me to record the masterpiece that is the Art of Fugue on a masterpiece of an instrument, the Lisbon Taskin.

Composed during the last decade of his life, the Art of Fugue consists of 14 Fugues (or Contrapunctus) and 4 Canons based on a single subject. It was Bach’s final and most accomplished exploration of contrapuntal composition. Although already viewed by his contemporaries as a master of the fugue, Bach sought to push the limits of his mastery by employing a unique subject, in D minor, to create his contrapuntal apotheosis. Each fugue increases in complexity and the original subject undergoes numerous transformations attempting to demonstrate all the possibilities of fugal composition - thematic inversion, rhythmic alteration, entire mirror images, a variety of national styles, augmentation and diminution. New themes are introduced in the second half of the work, yet they all derive from the original subject.

The final fugue that Bach ever wrote and the one that ends the Art of Fugue, Contrapunctus XIV, is incomplete. The third subject he introduces in this fugue is his own name B-A-C-H. The letters correspond to B flat, A, C and B natural (which is H in German). Just as a painter signs their masterpiece, this is Bach’s musical signature. Although Bach’s failing health has been given as the reason why it is unfinished, some leading Bach scholars now think that the end of the work was either lost or was never meant to be completed, Bach perhaps intending it to be a challenge for the player to solve. Yet there is a powerful metaphor in this compelling moment of rupture, after 80 minutes of an unparalleled achievement of divine complexity and beauty. Abruptly, it is over. Bach’s final work, like life, ends without resolution.

Bach notated the piece on four staves rather than on the usual two he employed for his keyboard works. He does not specifically state that the work is intended for keyboard (although this is stated by his son C. P. E. Bach who first published the work a year after Bach’s death). There was a strong, centuries-old tradition of writing keyboard counterpoint in full score for purposes of visual clarity, however, many scholars believe the piece was intended to leave open the option of scoring. Although I follow my teacher Gustav Leonhardt in believing it is a keyboard work, Bach’s works in general, more so than those of any other composer, can almost always be successfully transcribed because of their inherent completeness and universality. A string quartet, modern piano or any other combination of solo instruments can successfully and convincingly do justice to the work.

All instruments possess their own unique qualities, and the manner in which they can accentuate the intricacies of part writing differ. Whereas a pianist or violinist can simply play a theme in a given voice louder in order to highlight it, the harpsichord, unable to do this, uses articulation, touch, tempo and rhythmic variation to create a dimensional depth. Although more difficult to achieve, this “magnificent constraint”, the deployment of these techniques to explore expressivity and nuance, is everything.

Kenneth Weiss, Montauk, New York, June 2021

The Colares Taskin

© Nuno Ferreira Santos

Thanks mainly to the investigations of the musician and musicologist Bernard Brauchli, it is possible to trace much of the instrument’s history. It was bought in 2001 by the Portuguese Ministry of Culture from the heirs of the Marquise de Cadaval and incorporated into the collection of the National Music Museum. The instrument had been housed in the Marquise’s property in Colares near Sintra in Portugal, hence its name “The Colares Taskin”.

The Marquise de Cadaval, an ardent music lover, was a Venetian noblewoman who married a Portuguese Marquis and settled in Portugal in 1930. She received the exiled Italian King Umberto II when he and his family arrived there in 1946. To express his gratitude Umberto gave the Marquise the Taskin harpsichord. He had also received the instrument as a gift from the city of Turin in 1930, when he, as Umberto of Savoy, Prince of Piedmont, married Marie José of Belgium. It had been in the collection of the Turin Museo Civico, which had bought it 60 years earlier from the royal family of Savoy. In 1905 the museum published a photograph of the harpsichord indicating that it had “belonged to Clotilde of France”.

Marie-Clotilde, sister of King Louis XVI of France, had married Carlo Emanuele IV of Savoy in 1775 and settled in Piedmont. We have no record of the harpsichord between its construction in 1782 and its purchase by the Museo Civico in 1870, but its lavish decoration is indisputably worthy of a queen.

By being in Italy, the instrument escaped the fate of many other harpsichords in Paris during the French revolution: generally owned by aristocrats, they were used to light bonfires. Yet Italy was hardly a safe haven. Piedmont found itself in the midst of the Napoleonic wars, and Carlo Emanuele was forced to abdicate in 1798, after which the royal palace in Turin was ransacked. How the harpsichord survived the upheaval is unclear; possibly it was kept in one of his other residences. The instrument appears to have been generally well cared for. It was clearly not stored in a dusty attic or damp cellar, an infallible recipe for being attacked by woodworm and termites. The instrument has come down to us largely unaffected by insects, with the peculiar exception of one single sharp key and one leg of the stand that had both been eaten away by woodworm.

While the instrument escaped revolutions, wars and bugs, it faced another, more subtle form of destruction. By the 19th century composers began writing for the piano and the harpsichord was viewed as inferior - not only musically but technically. Many historical instruments suffered irreversible damage from well intended but ignorant repairs and restorations. Their strings were replaced with thicker ones than originally intended, and their soundboards reinforced with bars due to the higher tensions. Delicate parts of the action such as the jacks (the plucking mechanism) that deteriorated through oxidisation or wear were replaced with newly fabricated ones of bad quality, while the original ones were thrown away and lost forever.

In this respect, the Colares Taskin was lucky. The only real assault on the instrument was the insertion of heavy lead weights into both the keys and the jacks, a common practice in the early 20th century. The touch must have seemed too light for a pianist, but the adjustment spoils one of the main characteristics of harpsichord playing: the ability to feel the moment the string is plucked. Taskin did his best to make the keys as light as possible. His skill resided in the way he pared away excess wood from the key lever in such a way that it did not affect its stiffness, nor diminish the precision of the touch.

In 2016, the Museu Nacional da Música initiated the process of restoring the instrument to its former glory. Although it was in relatively good condition, the full restoration remained a daunting task. A harpsichord is a musical instrument but, unlike a violin or a guitar, it is also a machine. As well as purely acoustical considerations, a restoration involves taking care of a myriad of moving parts, often consisting of delicate components that have to interact smoothly. As luck would have it, the Marquise made very few adjustments to the instrument. When it arrived at the museum, the strings were thicker than those prescribed by Taskin, so the tension was immediately taken off them to avoid further damage.

In the first phase of the restoration, carried out by Ulrich Weymar of Hamburg, construction elements and small cracks on the soundboard were repaired. New strings were put on according to Taskin’s indications - the thicknesses according to gauge numbers stamped on the wrestplank: rouge for red brass, jaune for yellow brass and blanc for iron. Thanks to research over the last few decades we can now translate these gauge numbers into diameters in millimetres, and have learnt a lot about feedstock and fabrication processes to achieve wires very close to those of the 18th century. There is a considerable difference between the sound produced by these strings and those made of modern materials.

The beautifully lacquered decoration of the instrument and the stand were restored by the Portuguese National Laboratory for Research and Conservation of Cultural Assets.

In a final phase, I revived the musical capabilities of the instrument with a complete overhaul of the action. By removing the inserted lead the keys regained their original weight. Some of the key levers had warped over time and had to be straightened out. Many of the original jacks - the part of the action that holds the plectrum - could not be made to work reliably. It was decided to make a whole new set of jacks, copying the original ones by Taskin as closely as possible. The original jacks are now stored in the Museum.

The plectrums (also called quills) were historically made of the dorsal part of the rachis of bird feathers. They need to be tailored for each individual string to make an even touch and balanced volume from the bass to the treble. As they tend to break, a plastic substitute was found in the 1960s but although it is more durable than bird quill, the sound it produces is of a lesser quality. The quills used in the restoration of this instrument are from seagull feathers, ethically sourced during the moulting season.

Listening to this recording is listening to a journey of almost 240 years, and the restoration work of several artisans and artists.

Geert Karman, Lisbon, Portugal, June 2021

Technical description

The Colares Taskin has two keyboards with a compass of EE-f3 with 8’ 8’ 4’. Additionally there is a peau de buffle register and a buff stop that can be activated on both 8’ registers. There are 5 knee levers (genouillères): diminuendo, engage / disengage 4’, engage / disengage lower 8’, engage / disengage peau de buffle and lift / lower peau de buffle jacks. The coupler between the two manuals is of the traditional shove type.

In the wrestplank is stamped “FAIT PAR PASCAL TASKIN A PARIS. 1782”. The metal rose in the soundhole however is by Andreas Ruckers, a member of the famous family of harpsichord makers of Antwerp in the 16th and 17th century. The front board bears the inscription “ANDRÉ RUKUERS ANNÉE 1636” in gilded letters. On the soundboard the year 1636 appears twice, once in pencil between the 4’ and 8’ bridge and once in a painted ribbon near the spine.

The acoustical qualities of instruments by the 17th century Flemish makers were so esteemed by the French that a new instrument would be worth much more if it was based, if even partly, on one of these gems that were outdated in terms of musical practice. In the 1782 instrument parts of the soundboard bear traces of woodworm along what seems to have been the location of bridges of a virginal. It was therefore long assumed that Taskin re-used the soundboard of an old Andreas Ruckers instrument. A recent dendrological study has found that the treble part of the soundboard is indeed made of planks that must have been cut in the early 17th century. The rest of the instrument, the case, the stand, the action, the bass part of the soundboard and also the entire decoration of the soundboard, are all from the Taskin workshop.

Geert Karman

The Portuguese National Music Museum

The Museu Nacional da Música houses one of Europe’s richest collections of musical instruments, around 1500 exhibits dating from the 16th to the 20th century of mostly European origin. Of both erudite and popular traditions, some of these instruments are among the most precious national treasures of Portugal’s cultural heritage. The Museum is particularly notable for the quantity and quality of instruments manufactured in Portugal. These include the harpsichord by Joaquim José Antunes (1758), the violins and cellos by Joaquim Galrão, the guitars by Domingos Araújo and the flutes by the Haupt family. Other instruments are remarkable due to their previous owners and their considerable value and rarity, such as the harpsichord by Pascal Taskin, built in 1782 for King Louis XVI of France, the Boisselot & Fils piano that Franz Liszt brought from France in 1845, the oboe by Eichentopf, and the English horns by Grenser and Grunman.

The project for the creation of a music museum in Portugal dates back to 1911, and was an initiative of the musicologist Michel’Angelo Lambertini. The collection was later housed in the Lisbon Conservatory. In 1994, the Lisbon Metro and the former Instituto Português dos Museus, temporarily established the Museu Nacional da Música in the Alto dos Moinhos metro station. The collection will soon move to the Palácio Nacional de Mafra.

The museum has developed a consistent policy of acquisition and conservation of historical instruments, but also enabling them to be heard in concert and to be recorded. Most of these recitals take place in the museum itself, but there are also the so-called Concertos fora de portas such as the concert at the Centro Cultural de Belém with the Taskin harpsichord played by Kenneth Weiss that we can hear on this CD.

The restoration process of the instrument was both complex and meticulous, the museum and the restorers working closely together. Scholars and connoisseurs of the history of the harpsichord, as well as harpsichordists, were also consulted. The restoration of the Taskin harpsichord was without doubt a long awaited and important event for both Portuguese and international organological heritage. In recognition of this considerable multidisciplinary task, the Museu Nacional da Música won the APOM (Portuguese Association of Museums) Prize in the Conservation and Restoration Category in 2019.

This precious recording is the first to be made with the Taskin harpsichord and underlines one of the museum’s principal missions: to make organological heritage accessible to the general public by preserving and making available the sound of the instruments.

This project is the result of the enthusiasm, dedication and generosity of a multidisciplinary team of restorers and researchers, and of course the musician Kenneth Weiss, to whom the museum is immensely grateful.

Graça Mendes Pinto L., Lisbon, September 2021

Track list

1 - Contrapunctus I - 03:37

2 - Contrapunctus II - 02:41

3 - Contrapunctus III - 03:04

4 - Contrapunctus IV - 03:42

5 - Canon per augmentationem in contrario motu - 04:03

6 - Contrapunctus V - 04:11

7 - Contrapunctus VI - 03:57

8 - Canon alla duodecima in contrapunto alla quinta - 02:02

9 - Contrapunctus VII - 04:27

10 - Contrapunctus VIII - 06:07

11 - Contrapunctus IX - 02:54

12 - Canon alla ottava - 02:24

13 - Contrapunctus X - 04:56

14 - Contrapunctus XI - 07:13

15 - Canon alla decima in contrapunto alla terza - 04:24

16 - Contrapunctus XII - 05:21

17 - Contrapunctus XIII - 04:42

18 - Contrapunctus XIV - 08:37