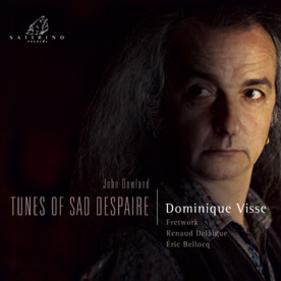

Satirino records · Dowland - Tunes of Sad Despaire

John Dowland, 1563 - 1626

Dominique Visse

countertenor

Fretwork

viol consort

Asako Morikawa, Reiko Ichise, Richard Tunnicliffe, Richard Boothby

Renaud Delaigue

bass

Éric Bellocq

lute & orpharion

Satirino records SR121 - released on 24th October 2012

Recording

Église de Marols, Loire, France, 18, 19 & 20 ix 2011

Instruments

Eric Bellocq

Orpharion - Ugo Casalonga, 2007, tuning ‘vieux ton’

Lute - Michael Haaser, 2008, (concept Liuto-Forte d’André Burguete), accord ‘Bellocq’ par tierces

Asako Morikawa - treble viol by Jane Julier, 1988, after John Rose

Richard Tunnicliffe - bass viol by Dietrich Kessler, 1968, after Henry Jaye, treble viol by Wang Zhi Ming, 2010, after John Hoskins

Reiko Ichise - tenor viol by Dietrich Kessler, 1965, after Henry Jaye

Richard Boothby - bass viol by Jane Julier, 2008, after Henry Jaye

Tuning

1/6 syntonic comma meantone

Sound engineer, producer, editing, mastering

Jiri Heger

Design

le monde est petit

Images

© Arthur Forjonel

Thanks to

Maurice Pezdevsek, Maire de Marols

Louis Daurat, artistic director, and the organisers of the Musicales d’Automne Festival

Reiko Arai, Émiko Bellocq, Josiane Frachey, Monsieur & Madame Dugas-Sauze, Pierre Pugnère, Jiri Heger, Aline Pôté, Arthur Forjonel & Supercloclo

The Auberge and the Café in Marols

The children of the school of Marols and their school master

This recording was made possible thanks to the generous support of the Commune of Marols and the Communauté de Communes – Pays de St Bonnet-le-Château

The Musiques d’Automne Festival

Madame Reiko Arai

Madame Emiko Bellocq

Marols is a remarkably charming village nestled in the Southern Monts du Forez. The history of this beautifully restored village goes back over many centuries, and its military and religious heritage can be admired from numerous breathtaking view points...

Marols is on one of the Santiago de Compostela pilgrimage routes. It has been the home of the Festival Musiques d’Automne for the last three years and in this way the village is able to add musical heritage to its own architectural heritage.

Press reviews

"From a young counter-tenor/director to one with venerable experience, Dominique Visse explores the doleful world of that professional depressive, John Dowland, in Tunes of Sad Despaire , accompanied by the viol consort Fretwork and lutenist Eric Bellocq and with occasional assistance from sepulchrally toned bass Renaud Delaigue. Visse’s faintly Mediterranean approach to Elizabethan English (bravo to him for tackling authentic pronunciation) emphasises an atmosphere perpetually on the verge of tearful precipitation, awash with a melancholy enhanced by the limpid sound quality." Rebecca Tavener, Agora Classica, March 2013

“..il s'agit donc d'un disque d'une grande poésie, temple que les amateurs de Dowland et de Visse ne manqueront pas de visiter.” Xavier de Gaulle, Classica

“Dominique Visse s'écarte de l'approche traditionnelle des Lute Songs. La présence d'un consort de viole en plus d'un luth l'encourage dans une voie moins méditative...On note l'empathie de chant de Visse avec la viole que le double, épousant les variations du crin et le boyau. Voix seule avec luth, avec consort de violes mais aussi voix, luth, violes et basse (de viole) doublée par le chant Renaud Delaigue. Cette dernière option nous faut un Flow my tears, ne ressemblant à rien de ce qu'on a pu entendre jusqu'ici de cet emblème de la mélancolie élisabéthaine. Le spleen s'y déploie fièrement et voluptueusement, la polyphonie ronronne sur ses graves comme une Bentley !” Sophie Roughol, Diapason

“L'album mêle pièces vocales et instrumentales et les violes de Fretwork complètent idéalement le timbre fascinant du contreténor.” Michèle Fizaine, Midi Libre

"Le contreténor Dominique Visse livre une interprétation passionnante d’airs mélancoliques de John Dowland (1563-1626), aux côtés du luthiste Éric Bellocq et de l’ensemble Fretwork.

"De ces chants de mélancolie, Dominique Visse restitue avant tout le caractère intime. Nulle proclamation du malheur ici, nulle volonté d’apitoyer : il s’agit bien plutôt de la transposition en musique du thème de la vanité, telle que s’y livraient, à l’époque même de Dowland, les peintres de la Renaissance. Ce sont donc ténèbres, ombres, tristesses et larmes que chante ici le contreténor en des musiques alenties – ne font exception que quelques interludes, telle la chanson de rue « Five knacks for ladies », dont l’atmosphère et la fantaisie rythmique tranchent nettement avec le ton général de l’album. La voix se fait miroir des pensées intimes, de ces lamentations pour soi-même. Pour autant, ces chansons accompagnées au luth ou à l’orpharion sont tout sauf des sanglots : tout l’art de Dominique Visse tient à la façon dont il façonne ici un espace sonore ni trop vaste, ni trop étriqué – il faut l’imaginer comme celui du cabinet où l’on se retirait pour méditer en chanson. L’accompagnement d’Éric Bellocq, au luth et à l’orpharion, ne trahit pas – bien au contraire – cet espace intime, tout comme le consort de violes Fretwork, prolongeant admirablement le chant du contreténor dans « Now O now I needs must part », qui conclut cet album à écouter avec toute l’attention que réclament les voyages intérieurs." Jean-Guillaume Lebrun, La Terrasse,

avril 2013

“Dominique Visse, peut- être une des incarnations actuelles de l’âme tourmentée, leur prête (aux lute songs) une voix sans affect, veloutée et fragile. Sa diction sans reproche nourrit des scènes aux ombres portées par la chandelle – En mélancolique ambigu, Dominique Visse prend des libertés avec Dowland et le travesti, parfois en remplaçant le luth (Eric Bellocq) par un consort de viole (l’ensemble Fretwork), et d’autres fois en partageant sa partition avec Renaud Delaigue(basse) : le résultat n’en est que plus troublant.... Mais la mélancolie ne vit pas que d’elle-même, la part sombre a besoin de lumière. Et les Ayres alternent avec des pièces instrumentales ou des pavanes plus légères. Ainsi passe une heure qui évite le désespoir pour approcher le calme intérieur.” Albéric Lagier, Muzikzen

“Dominique Visse possède un don spécial pour les rôles de satyre ou de duègne, et pour les cantates comiques ou grivoises. Coassant, histrionique, c’est un artiste qui n’engendre habituellement pas la mélancolie. Sauf dans le cas de ce disque consacré à Dowland. La suavité bien connue de Fretwork, une prise de son à l’estompe, et sa propre sobriété, tout cela lui donne une voix plus rajeunie et lisse que jamais. Heureusement, Dominique Visse ne se contente pas de pasticher d’Alfred Deller, même s’il en imite plutôt bien la grâce nonchalante. Son talent dramatique lui permet de donner du caractère et de la variété à ce programme. Il faut également noter la précision de la prononciation restituée, la limpidité de la notice signée par Richard Langham Smith, professeur au Royal College of Music, et reconnaître la volonté de mêler aux tubes du compositeur quelques titres plus rares. Mais le principal atout de ce disque réside dans la richesse des accompagnements réalisés pour luth et consort,alors que la polyphonie est souvent moins perceptible lorsque le luth seul doit l’assumer. Encore plus intéressantes, les versions à deux voix de certains airs, dont « Flow my teares ». Renaud Delaigue y est remarquable, comme toujours. Une bonne surprise, moins désincarnée que la proposition de Gérard Lesne, plus contrastée que celle de Damien Guillon, pour en rester aux réalisations françaises.” Olivier Mabille, Resmusica

Dominique Visse, poignant dans les chants mélancoliques de Dowland

“...Mais à la différence des romantiques, la mélancolie est abordée par Dowland avec distance et abstraction, selon des règles précises, pour satisfaire une demande alors très en vogue. Il n’empêche, ces airs (Ayres) possèdent souvent une profonde expressivité, et jouissent sur ce disque édité chez Satirino d’une interprétation pure et exquise du contre-ténor Dominique Visse. Ici, accompagné par l’excellent consort de violes Fretwork, on admire l’immense pureté de sa ligne vocale, son timbre cristallin et irréel qui sied à merveille aux « pleurs de l’âme » et autres états psychologiques douloureux mis en avant dans les poèmes.” musicaeterna.fr

“Dominique Visse is a wonderful sparkling singer with a non-vibrato countertenor voice. With a remarkable intonation he crosses the essence of the melody and so the soul of the music. His voice is flexible and sounds self-evident. A joy to listen to. A few pieces are duets, sung by Visse and bass Renaud Delaigue, a French singer who makes a wonderful mix with Visse’s timbre. We also hear lutist Eric Bellocq and the viol ensemble Fretwork.” Musicframes.nl

Liner Note

Taking into account the context of Renaissance English song, listening to a recording of Dowland lute-songs is tantamount to eavesdropping through a keyhole when you shouldn’t: clandestine voyeurism even. Singing to the lute was often an intimate business, and people did it alone, frequently accompanying themselves. The idea of singing Dowland Ayres to an audience—even in their madrigal versions—would most likely have been unusual if not unknown.

Lute-songs of this period were known as ‘Ayres’. One William Barley published four with bandora accompaniment in 1596 but the form really took off in the following year with John Dowland’s first book. The fashion for the form, presented in Dowland’s format, lasted for some 25 years. Both in the way the scores were printed and in his titling Dowland made clear the variety of ways in which the pieces could be performed. The 1597 set was entitled:

First Booke of Songes or Ayres of foure parts with Tableture for the Lute: So made that all the parts together, or either of them seuerally may be song to the Lute, Orpharion or Viol de gambo.

They were published in what has been called ‘tablebook-format’, in tall folio books where the printing was aligned to a quartet of performers sitting around a table facing inwards: a luxurious and unique way of presenting the printed music. But for solo, self-accompanied performance the same score could be used since it presented the lute part in tablature: a notation which showed where to put the fingers on the frets rather than indicating the pitches.

Many reports of the context in which the songs were performed have survived. A 1599 diary entry of one Lady Margaret Hoby, for example, records the following after-dinner activity:

‘... after dinner I dressed up my Clositte and, to refresh my self being dull, I plaied and sunge to the Alpherion’ (Orpharion — a metal-strung lute).

Thomas Morley, another lute-song composer of the era indicated such intimate performance in the preface to his 1597 collection:

'I haue set them Tablature wise to the Lute in the Cantus booke for one to sing and plaie alone when your Lordship would retire yourself and bee more private.’

Dowland’s biography is important to the genre and he can be seen as the father-figure of the form, not only because his song known as ‘Lacrime’ became internationally celebrated and the subject of many variations but also because of his travels. His birthplace is disputed but by 1580 he was in France in the service of Sir Henry Cobham, the English Ambassador. It was at this time he converted to Catholicism and he blamed his religion for his failure, on his return to England, to obtain a place among the Queen’s musicians in 1594 despite his reputation and achievements which included obtaining a Bachelor of Music degree from Oxford in 1588 (later he also obtained one from ‘the other university’ – by which, at that time, one meant Cambridge). He subsequently embarked upon a tour of Europe with the intention of studying with the highly reputed model Madrigal composer Luca Marenzio who resided in Rome, though it would seem that he never reached this city. We know, however, that he visited Venice, Padua, Florence and Ferrara. He certainly corresponded with Marenzio whom he esteemed above all others, printing a letter from him in the substantial prefatory material to his 1597 book.

The ambition to study with Marenzio was hardly surprising as this composer was revered as the instigator of a new way of marrying poetry and music. English treatises of the period absorbed the techniques of the Italian Madrigal composers and theorised them into instruction books for would-be English composers. Thomas Morley, already mentioned as a composer contemporary with Dowland, was the author of one such manual A Plaine and Easie Introduction to Practicall Musicke of 1597 which contained a section based on the practice of Italian madrigalists: ‘How to dispose your musicke according to the nature of the words which you are therein to express’. Although it may seem obvious to those familiar with madrigal singing, Morley reminded his readers of the most basic of principles: ‘you must haue a care that when your matter signifieth ascending, high heaven, and such like, you make your musicke ascend: and by the contrarie where your dittie speaketh of decending ... you must make your musicke descend’.

The various theorists went increasingly deeply into the techniques of composition and particularly into the new world of harmony and rhythm: the beginnings of Baroque expressivity. Charles Butler, looking back over the golden age of lute-song in a 1636 treatise entitled The Principles of Musik in Singing and Setting writes of the expressive power of the descending semitone: a device often used by Dowland: ‘Woords of effeminate lamentations, sorrowful passions, and complaints ar fitly exprest by the inordinate half-notes’, he writes. Morley had already identified other intervals in the 1597 treatise already mentioned: ‘Flat thirdes and flat sixes, which of their nature are sweet’, he remarks, while ‘to express sighes you may vse the crotchet or minime rest’ ... The repetition of ‘sorrowful’ words is also commonplace. It should also not be forgotten that lute-song composers mirrored the expressive devices of the vocal part in the lute accompaniments.

Such remarks are quintessentially of the turn of the sixteenth century where the song composers of, for example, the Florentine Camerata—such composers as Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini—not to mention Monteverdi—were developing what Monteverdi called the ‘Stile Rappresentativo’ where the words expressed emotions rather than described them. A combination of influences from the French chanson with an interest in these new developments in Florentine music were important motivating forces in English music during the first part of the seventeenth century.

The popularity of rhetoric and a fashion for melancholy were also over-arching, particularly in the case of Dowland’s Ayres. Apart from the rhetorical devices advocated by Morley and Butler, there was a more general principle at work in much of the poetry set by the lute-song composers, where the rhetorical ‘proposition’ to be explored is encapsulated in the first words of the poem. Examples of this procedure are common in Dowland. On the present recording we may mention in this respect ‘Go Cristal tears’; ‘Sorrow come’ (a variant on ‘Sorrow stay’); ‘Goe nightly cares’; ‘Come heavy sleep’, not to mention the most famous ‘Flow my tears’.

Dowland’s predilection for melancholic texts has often been remarked upon: ‘Semper Dowland, semper dolens’ was the quip by which he is remembered, ‘Always Dowland, always melancholy’. In the context of Elizabethan song this was by no means unique: it was merely a musical expression of an emotional—even philosophical—concept already ingrained in English thought. In 1586 Timothy Bright had published a Treatise of Melancholy and, among other books dealing with Elizabethan melancholy, Nicolas Breton had brought out a book of poems entitled Melancholic Humours in 1600. The major tome, however, was Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, published in 1621 but written earlier, during the heyday of Dowland’s melancholy. Though published in Latin, its English title promised the reader an explanation of ‘What it is with all the kinds, causes, symptomes, prognostickes & severall cures of it’. For its author its causes had a lot to do with God punishing miscreants; bad diet; the ‘humours’; love-melancholy and a host of other things: an essential read for students of Dowland.

‘Go Cristal Tears’ comes from the composer’s First book of songs. It illustrates the problem of fitting two stanzas to one musical idea and how this is craftily achieved. Expressive devices expressing the text in music were often crafted to fit the first verse but in clever hands could be made to fit more than one stanza. In this song the word ‘weep’ (into his Lady’s breast) is highlighted first time round, but in the second stanza the same musical emphasis falls on the word ‘ice’, most appropriately, on the same musical idea. The text, like many madrigal texts both in Italy and in England, is Petrarchian, with its typical use of contrasts between the heat of passion and the ice of rejection. More metrical and regular is the song ‘If my complaints’ whose motto is reserved for its final line: ‘I was more true to Love than Love to me’. ‘Sorrow come’ is a textual variant from a 5 part version by William Wigthorp of the original version in Dowland’s Second Book of 1600 whose text read: ‘Sorrow stay’.

Thomas Simpson’s printing of a Pavan (Paduan) is very doubtful in its attribution to Dowland but it is a welcome relief from the minor intervals and falling trajectory of the composer’s melancholy songs. Simpson had found more success in Hamburg than at home and in this four-part piece with two part-crossing treble viols (not typical of Dowland and more in a German style) he employs division techniques in the latter part of the piece, published in 1621.

Dowland composed many pieces for lute and it has been an immense task to gather them into a modern edition, the composer himself having failed to achieve his aim of a collection of his best compostions. Many are preserved in the collection of the ‘other university’, the Library of Cambridge University, from which Dowland later obtained a second degree. ‘What if a day’ seems to be a song of which no texted version survives. The already-mentioned ‘division’ technique is used in this piece, and also in ‘Dr Case’s Pavan’ where a simple version of a stanza is followed by a variation where the linear parts are ornamented with quicker notes: a principle established in Italy—known as passaggi—in instrumental music from the early-mid sixteenth century.

‘Fine knacks for Ladies’ is in the tradition of a street-vendor’s song, in this case with fancy rhythmic quirks over a classical structure.

‘Goe nightly cares’ comes from Dowland’s last published of book Ayres, A Pilgrimes Solace of 1612 in which the composer seems to be bidding farewell to composition, having returned to England after having been fortunate enough to be employed in ‘Kingly entertainment in a forraine climate’. He cites ‘eight most famous Cities beyond the seas’. In this song he bids ‘adue’ (adieu) to life: one of his darkest songs.

‘Flow my tears’, Dowland’s ‘Lacrime’ is presented as a duet on the present recording: unusual but effective in stressing the basso continuo structure which, taken from Italy, was establishing itself at this time.

The anonymous ‘Lamentacion’ of the Lord of Dehim provides an opportunity to hear the Orpharium weaving diminutions on a decending bass, appropriate for a lament while the following piece, ‘In darkness let me dwell’, is taken from a collection of songs published by Dowland’s son Robert, but containing pieces attributed to his father John. Notable is the curious expressive word-setting of the phrase about music making ‘hellish iarring (jarring) sounds to banish friendly sleep’. The various intervallic, harmonic and rhythmic techniques suggested by Morley, already mentioned, are forcefully in evidence here as they are, in a different way, in ‘In this trembling shadow cast’ from Pilgrimes Solace, more like a contrapuntal piece in which the cantus takes the top line. The opening, on a dissonance, is particularly striking.

The Earl of Essex, Robert Devereux, a celebrated courtly poet is the author of the text of ‘From Silent Night’ dedicated to ‘my louing country-man Mr. John Forster the younger, merchant of Dublin in Ireland’. As with several songs from the late collection—it comes from The Pilgrimes Solace—the setting is more like a consort-song in which the singer adds counterpoint to the setting rather than singing a self-contained song.

‘Come heavy sleep’, sung as a duet, returns to the style of the first book of that golden year 1597 when the form to which this recording is indebted was first born. It is followed by a consort version of another song from the same collection and we end with ‘Now o now’ another gem from Dowland’s initial—and initiative—volume.

Richard Langham Smith

Track list

1 - Go crystall teares

- 4’24

Dominique Visse, Fretwork, lute

2 - If my complaints

- 4’21

Dominique Visse, Renaud Delaigue, Fretwork, orpharion

3 - Sorrow come - 3’46

Dominique Visse, Fretwork

4 - Paduan par John Dowland/Thomas Simpson - 4’59

Fretwork

5 - What if a day

(Poulton n°79) - 1’49

Lute

6 - Fine knacks for ladies

- 2’03

Dominique Visse, Fretwork, lute

7 - Goe nightly cares - 3’37

Dominique Visse, Fretwork, orpharion

8 - Flow my teares

- 4’51

Dominique Visse, Renaud Delaigue, Fretwork, lute

9 - Anonyme - My Lord of Dehims Lamentacion, manuscrit Cambridge Dd.2.11 fol.40v - 2’18

Orpharion

10 - In darknesse let mee dwell

- 4’35

Dominique Visse, Fretwork, orpharion

11 - In this trembling shadow - 3’46

Dominique Visse, Fretwork

12 - Away with these selfe louing lads

- 1’59

Dominique Visse, Fretwork, orpharion

13 - Dr. Case’s Pauen, Poulton N°12, diminutions pour les reprises d'Éric Bellocq - 4’28

Lute

14 - From silent night

- 4’14

Dominique Visse, Fretwork, lute

15 - Come heauy sleepe

- 4’37

Dominique Visse, Renaud Delaigue, Fretwork

16 - All ye whom loue of fortune or fortune hath betrayd

- 2’20

du first booke of songs or ayres

Fretwork, orpharion

17 - Now, O now I needs must part - 7’33

Dominique Visse, Fretwork